By Brandon & Kristin Hendrickson (schoolsforhumans.org)

We thought that we understood the power of Imaginative Education (IE).

We were wrong.

Let’s back up — we’re a pair of educators! Kristin’s a Montessori teacher, and Brandon’s a high school humanities teacher. We’re not newbies to IE. We’ve been crafting our lessons with IE for years (and to delightful results). We’ve read umpteen different books by Dr. Kieran Egan. Heck, we’ve spoken at the last three Imaginative Education Research Group (IERG) conferences — and we love IE so much that we’re opening an IE grade school next year!

So you might assume we had IE down cold. We thought so, too! And then came our great crisis.

We take seriously a quote that Kieran Egan’s cites, from the psychologist Jerome Bruner:

Any subject can be taught effectively

in some intellectually honest form

to any child

at any stage of development.

Kids, we’re convinced, aren’t the fools that contemporary schooling assumes them to be. If we engage their minds the way they’re designed to make sense of the world — as opposed to the dry information-pushing that schools often do through worksheets and textbooks — they can understand (and fall in love with) topics that are quite advanced.

To test this out, this last fall we started up a weekly class for 5-, 6-, and 7-year-olds on ancient history. And philosophy. And science. Oh, and cooking.

We called it “Young Philosophers”. (Sound too ambitious, yet?) And things went wrong from the moment the kids walked through the door.

Did we say walked? We should have said tumbled, scrambled, or cascaded! A superorganism of rambunctiousness entered the room, bringing the joy of total entropy to anything it touched.

We need to emphasize two things here: One, we’ve taught young kids for more than a decade. We’re pros at engaging even the most boisterous kids. Two — none of that helped us at all. Nothing prepared us for this.

Lead the kids in deciding upon classroom rules? Forget it! Snag kids with an absurd philosophical question? Didn’t work! There’s a theoretical minimum of order — a floor of shared attention — that must be in place before more order can be erected. Meanwhile, kids were crawling on the furniture.

Everything failed — until Kristin opened her mouth to tell the story of Socrates.

What can you do when a class of students is so wild you can’t think straight?

Tell a story.

She didn’t tell some simple, saccharine, “kid-friendly” story. Rather, she laid out the severe world of Athens into which Socrates was born: a village that prized glory, and cast aside anyone who lacked it.

Are you the fastest? The strongest? Can you throw a rock farther than anyone else in town? Then you have worth. In fact, you may have immortality — songs may be sung about you long after your death!

Are you not any of those things? Well, then you are worthless. You’ll be forgotten — certainly after you die, and perhaps even while you live.

The kids were riveted — spellbound by ancient history. And from that, we built more focus and order: conversations about what makes someone valuable, and eventually (following Socrates) what it means to be “smart”.

It was glorious. And then we moved to a science experiment… and things fell back into anarchy.

After the day was over and the kids had left, we thought: huh. The one part of the three-hour lesson that had succeeding in capturing the kids’ focus was the story which we had constructed on IE principles. (If, when you read the above account, you thought worth/worthlessness is an abstract binary opposite, give yourself ten IE points!)

Obviously, we wanted to repeat that success with the next week’s history story. But how could we bring more IE into the lesson? We realized the answer: the science lesson.

That first week, we had conducted a hands-on science lesson on bananas. (Each month, we focus on one food item.) Perhaps that would have worked wonderfully with more self-controlled kids… but ours made them into guns and parts of anatomy that we’ll leave to your imagination. Holes were bored into the fruit just for the pleasure of making that mucky smooshing sound.

The hands-on science lesson did not, in other words, succeed at teaching science. It was time, we said, to break out the IE!

And so we did, asking, what’s the story of the banana? We’re not trained as scientists — in fact, we both more-or-less avoided science classes in college (Kristin majoring in English, Brandon in Religious Studies and History). So we went to Google, and pieced together the epic story of human–banana co-evolution!

(Brief excursus: ohmygosh bananas are amazing! They begin in New Guinea as football-shaped, bitter, green fruit with hard seeds, and, through a series hilarious hijinks including mutating and being cloned, have become the curvy, sweet, yellow seedless fruit that children adore — with Alexander the Great, the Bantu expansion, Arabic, and Jamaica all playing key roles.)

At the end of the lesson, one girl raised her hand: Why, she asked, do bananas change color? Yeah, we thought, why DO bananas change color?! Back to Google!

And here we hit an unexpected snag: the internet is terrible for explaining science.

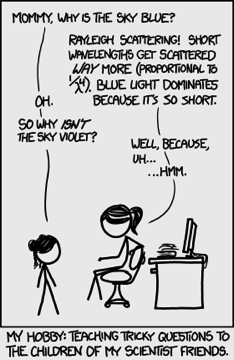

At least, that’s been our experience of it. The net abounds with sites devoted to explaining science — alas, nearly all of them fall into one of two errors: (1) they assume a college education’s worth of previous understanding, and are too dense for the lay reader, or (2) they “explain” things by simply slapping scientific names on them. A classic example, from xkcd:

(Source: http://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/sky_color.png)

So we turned to our friends with degrees in the sciences. For hours we grilled them on the phone, connecting the specks of info we had found online into webs of understanding (connecting to what, in IE are called “kinds of understanding“), and then patterning those webs into an IE framework, using riddles, metaphors, and abstract opposites. We invite you to take a look at the video we shot of the lesson.) What follows is a simplified version of it.

Why are bananas green? (Why are most plants green?)

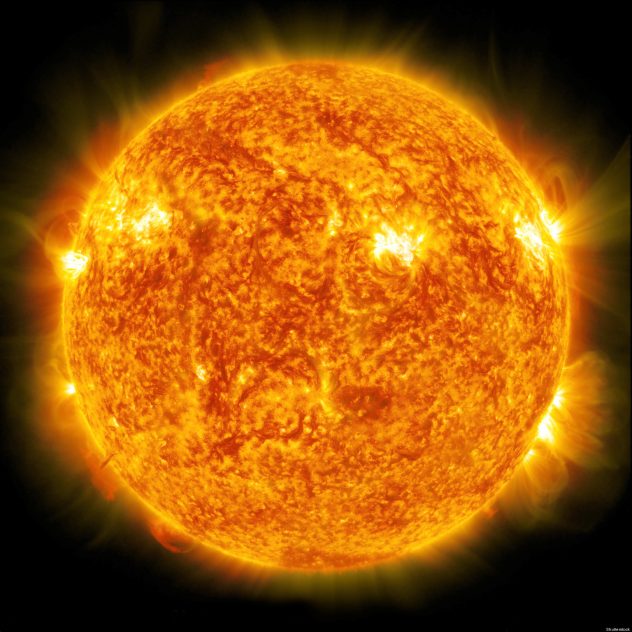

The Sun shoots out light in tiny balls [photons]. It shoots these balls out faster than a cannon — they’re literally the fastest thing in the Universe! This gives them tremendous power, which is a huge danger — the balls should destroy the tiny rooms that plants are made out of [cells].

So why do plants like the Sun, instead of fearing it?

Thankfully, the plants have designed tiny devices — imagine them as green baseball mitts — to catch the balls of light, and to use that power for good [chloroplasts]. The baseball mitts hold the balls of light, and then spin them frantically around, storing the energy [chemical bonds]. They use that energy to grab bits of breath [CO2] from the air, and to squeeze the pieces of breath together to make more bananas [sugars]!

That’s why bananas start off green: to grab sunlight, and to use the energy of that sunlight to squeeze together breath to make bananas.

Why are bananas yellow?

Sometimes, the baseball mitts [chloroplasts] accidentally slip, and drop the balls of light — which go caroming around the banana, smashing through the tiny rooms. It’s terrible! So the banana has created tiny pillows to cushion the blow of these slipped balls [carotenoids or antioxidants]. They’re bright yellow — and are similar to the tiny orange pillows inside of carrots, and the tiny red pillows inside maple leaves.

So bananas are yellow because that’s the color of the tiny pillows that cushion the rooms from the dropped baseballs.

Why aren’t bananas always yellow, then?

Secretly, the bananas are yellow, even from the beginning — the tiny pillows are always there. You just can’t see it because of the green baseball mitts.

The banana gets rid of the green baseball mitts, which is strange — you’d think the plant would want to keep them, because then it could keep getting energy!

So why do bananas turn from green to yellow?

The bananas turn from green to yellow in order to tell animals to devour them.

Wait, why would a plant want to be eaten?

A good mother kangaroo keeps her babies close.

A good mother bear keeps her babies close.

A good mother plant sends her babies far, far away!

A seed is a baby plant. And if a seed grows up right next to its mother plant, it won’t be able to get much sunlight — because the mother plant’s leaves will block it!

So how does a good mother plant get rid of its babies?

A maple tree puts spinners on its babies, so they won’t fall straight down.

A dandelion puts parachutes on its babies, so they’ll get blown far away.

Brilliant, huh? But a banana has an even more brilliant solution: it pays animals to carry its babies away, and plant them in good soil.

How does a banana pay an animal?

Well, what do animals want? Food — and sugar, especially! So the banana plant surrounds the babies with sugar — sugar that, remember, it made from squeezing together breath from the air — so the animals will eat it!

The animal eats the fruit, swallows the seeds, and walks away. Later, it poops out the seeds —and the seed grows in the animal’s poop! (Seeds love poop.)

But there could be a problem — how can an animal tell that a plant is full of sugar, and wants to be eaten?

The plant has a way to advertise — it changes the color of the fruit to something bright and strange. This is a color-coded way to yell to the animals HEY, COME AND GET SOME DELICIOUS SUGAR!!!

So bananas turn from green to yellow in order to tell animals to come eat their seeds. And they want animals to eat their seeds, so the young plants will grow up far away, where there might be more sunlight.

But bananas don’t have seeds!

Don’t tell them that! The first bananas had seeds, but then a human found this one strange mutant banana that lacked them. The human loved the fact that the banana was so soft — he valued his teeth — and so he snipped off the root of that banana tree, and replanted it. And, voila, more seedless bananas!

So all of the parts of a banana were designed long ago to grow seeds, and pay animals to take them far away. It’s only been a little while since bananas stopped having seeds — and the rest of the fruit hasn’t changed.

So…why do bananas turn brown?

In part, this is because bananas get old and die. Brown is the color that comes when all the other colors mush together.

But there’s another reason, too! There’s a special gas [ethylene] that bananas squirt out in order to turn their skin from yellow to brown.

The gas is unbelievably, remarkably… stinky! Why?

No one’s totally sure, but here’s one idea: if you’re a banana plant hidden in the thick foliage of the rainforest, what if animals can’t see you?

You can stink.

We humans think that rotten bananas smell disgusting. But lots of animals (like monkeys) think rotten bananas smell heavenly! So bananas scream to the monkeys PLEASE COME DEVOUR ME I’M RIGHT HERE AND AM SOOOOOOO DELICIOUS JUST FOLLOW YOUR NOSE!!!

And they “scream” by being stinky.

So: one of the reasons bananas turn brown is to tell monkeys where they are — so they can be eaten!

———

How IE Saved Our Class

So: what did we learn from diving whole-hog into Imaginative Education… in order to save our class?

First, the kids were riveted. Behavior problems plummeted during the lesson.

IE grabs the whole mind.

— including the parts traditionally dedicated to mischief-making!

Second, the kids wouldn’t shut up about it! Parents contacted us, telling us that their kids were repeating the lesson at dinner tables weeks afterwards.

IE is viral education.

Third, the kids learned real science. They didn’t memorize science-y terms, but glimpsed the connections between sun, air, plants, and animals. They learned about the carbon cycle. They learned about the dangers and promises of energy. They learned about human–plant co-evolution — and about monkey–plant co-evolution. They even learned about antioxidants! IE is real education.

We’ve learned, in short, that IE is more powerful than even we — as IE lovers — dreamt could be possible.

You’ll, perhaps, note some scientific gaps and errors in this lesson. Some of that may be because the above is a summary of a half-hour lesson — but some might really be an error in our understanding of the science! (Like we said, we’re humanities majors!) If you have any suggestions on how to improve the lesson, we’d love to hear them — send them along to [email protected].

Since those first weeks, we’ve been improving Young Philosophers. We’ve gone farther abroad in our Ancient History — kids have learned the stories of the Buddha and Confucius. And we’ve gone deeper in our science — kids have learned the biology, chemistry, and physics of onions and salt. (Teaching the atomic physics of salt — how combining a dangerous explosive with a flesh-dissolving gas creates the thing your brain needs in order to think — has been particularly vibrant.)

We’re looking forward to launching new IE lessons for the rest of the year. And we’re delighted to imagine: what could learning look like, in the primary grades, if we assumed that children were brilliant — and taught them through the IE toolkit of riddles, metaphors, and epic stories?

The question is: How intellectually vibrant could grade school become?

Hi Brandon and Kristin

Thanks for this report from your classes. I liked it very much and think I can relate a lot to what is happening in my classes except that it is on high school level meaning that stories have to deal with things which interest these guys – typically mysteries, human conflicts, LOVE, even shopping, drugs, tv series they watch etc. But still to me the basic idea seems the same so Thanks again for sharing your thoughts.

Brian

I’ve forwarded your comment to Brandon and Kristin, Brian. The idea IS the same–a “story-form” engages the emotion with the content/knowledge. It moves humans–of all ages!

I agree Brian. Pepper the same with relevance. It creates interest and grows curiosity.