Megan Sandham is a Grade 3 teacher in Delta, BC and a graduate student in Imaginative Education. You can check out @grays3rdgraders on Twitter to follow her students’ adventures.

“How many kids do you think are living on Earth, right now?” I asked the 19 faces staring at me.

A bunch of eager hands shot up, waving impatiently in the air.

“A quadrillion.”

“25 million.”

“35 million.”

“Infinity – because there are always people being born and there are always people dying.”

This is how I started our class exploration of identity this year.

Identity is a topic I love exploring with my students. In the past, however, I’ve always felt like something was missing. Sure, my students were able to demonstrate a concrete understanding of identity and could share some basics, but it always felt a bit too superficial. I wanted the learning to be “more”; more engaging, more thoughtful, more meaningful, more connected, more memorable. I chalked up this lack of substance to my students’ ages. I mean, how deep can 8 and 9 year old kids really get? The answer, it turns out, is pretty deep.

But first, a little background. In September of this year, filled with excitement and a healthy dose of apprehension, I began my graduate studies in Imaginative Education (IE) at Simon Fraser University. IE, for those unfamiliar with it, is an approach to education that focuses on engaging the feelings and imaginations of teachers and learners (Egan & Judson, 2016). Emotion is at the heart of all learning. When we feel something about a topic, we are much more likely to be invested and engaged in our learning, and as a result, are more likely to connect to it, remember it, and internalize it in a meaningful way. The best way to accomplish this, according to imaginative educators, is through the use of cognitive tools. These tools, when used purposefully, “can make students’ learning more efficient and effective, and can make teaching and learning more interesting, engaging, and pleasurable for all” (Egan & Judson, 2016, p.5). This approach challenged my beliefs about education and I was excited about the possibilities.

In BC, much of the curriculum we are expected to follow centres around the core belief that content should be developmentally appropriate and based on children’s lived experiences, beginning with concrete ideas and moving towards more abstract ideas as children make their way through the system (Egan, 2002). What if this belief was holding my students back? What would happen if, instead of moving from simple to more complex ideas, I moved between them? Armed with the imaginative educator’s set of cognitive tools, I decided to find out.

Which brings me back to the beginning of this piece. Rather than starting with something super concrete, like a basic definition of identity, I decided to start with what I thought was emotionally engaging about identity. How could I help my students see the wonder in the topic and convey why it should even matter to them? After my students shared some guesses about the World’s population, I projected the World Population Clock onto the screen. We discovered, to our amazement, that there are approximately 7.8 billion people living on Earth! My students were shocked by the sheer magnitude of the number and fascinated by the constantly changing tallies:

“Why are the numbers changing so fast?”

“Because there are always people being born and there are always people dying.”

“It’s so sad that there are so many people dying all the time.”

“But look! There are more people being born than there are people dying!”

Once we finished discussing the clock and the information it gave us, I had my students think about the billions of people on the planet and asked them if any two people living on Earth are exactly the same. After some debate (aren’t identical twins the same?), I threw caution to the wind and embraced Imaginative Education’s belief that “while children do, of course, deal with some aspects of their world in a “concrete” way, they are also abstract thinkers” (Egan & Judson, 2016, p.28) and shared the following quote:

All that we are is story. From the moment we are born to the time we continue on our spirit journey, we are involved in the creation of the story of our time here. It is what we arrive with. It is all we leave behind. We are not the things we accumulate. We are not the things we deem important. We are story. All of us. (Richard Wagamese, n.d.)

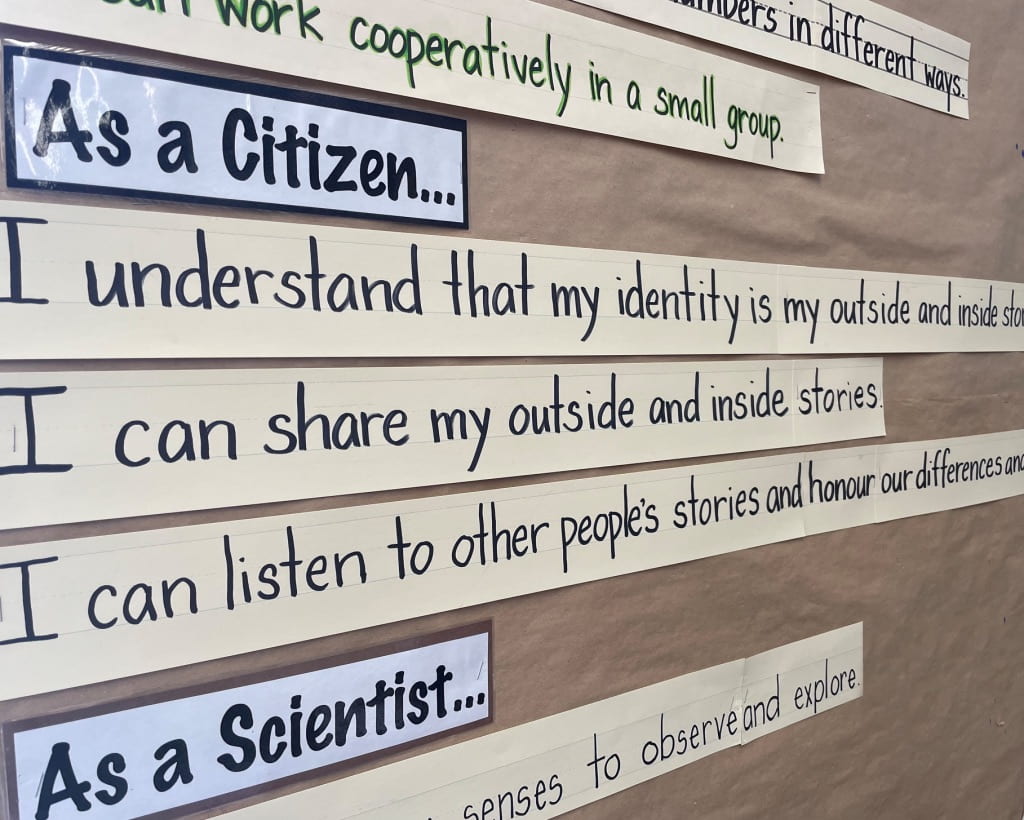

Every single person on Earth, no matter who they are, or where they live, has an outside story and an inside story. These stories, shaped by so many factors, are what make us who we are – what make us unique. No two people are exactly the same, and although we have many differences, we also have many things in common. What is your outside story? What is your inside story? What are the things that make up your identity and how does knowing your identity connect you to yourself, to others, and to the world around you? By using the cognitive tool of story, and by identifying the binary oppositions of outside/inside and visible/invisible, I was able to shape our learning in a way that helped my Grade 3 students see the emotional significance of identity, and already, our discussions were more meaningful and interesting. Encouraged by this success, I went one step further and introduced a metaphor (gasp!) to enrich our exploration.

Every single person on Earth, no matter who they are, or where they live, has an outside story and an inside story. These stories, shaped by so many factors, are what make us who we are – what make us unique. No two people are exactly the same, and although we have many differences, we also have many things in common. What is your outside story? What is your inside story? What are the things that make up your identity and how does knowing your identity connect you to yourself, to others, and to the world around you? By using the cognitive tool of story, and by identifying the binary oppositions of outside/inside and visible/invisible, I was able to shape our learning in a way that helped my Grade 3 students see the emotional significance of identity, and already, our discussions were more meaningful and interesting. Encouraged by this success, I went one step further and introduced a metaphor (gasp!) to enrich our exploration.

Metaphor, and its use in teaching, is powerful, because “it doesn’t simply describe connections that are already there but rather it establishes connections and new ways of seeing things that were not there before our metaphoric power created them” (Egan & Judson, 2016, p.43). In an attempt to harness this power, I used the metaphor of a picture book to help my students see identity in new ways. Each one of us, I proposed, is like a picture book, made up of an outside story and an inside story. You can look at the picture on our cover and discover a piece of our outside story, and then you can open us up and see more pictures that add to our outside story. Once you have looked at our pictures, you can read the words printed on our pages. These words tell our inside story. When our outside and inside stories come together, they make up our identity. Our outside and inside stories help us learn about ourselves and others. Our stories can connect us to people who are the same or different from us and can help us understand other people’s experiences.

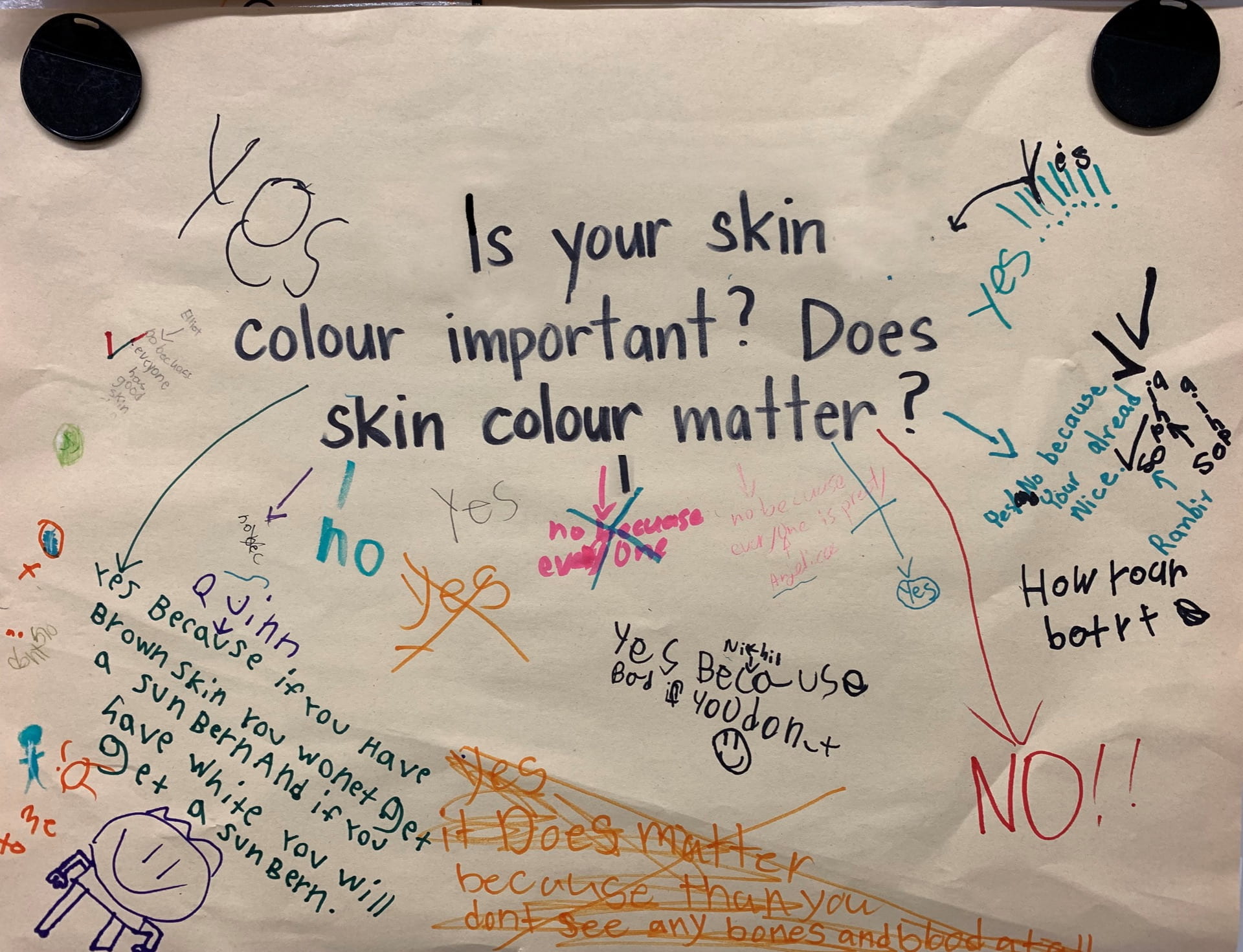

Over the course of several days, we looked at different images of children. I projected one picture at a time onto the board and recorded what my students noticed and wondered about the kids in the photos. These observations and questions led to some really meaningful discussions about important things, including race, gender, ability, and diversity, and we came to the conclusion that while our physical appearance can be an important part of our identity, it can’t tell our whole story. People can make assumptions about who we are and what we are capable of based on our physical characteristics. These assumptions can be false and hurtful, can make us feel “less than”, and can lead to different types of discrimination. We also concluded that there are so many important things that make up a person’s identity that are invisible – we can only “see” them if someone is comfortable sharing them with us. My students demonstrated so much learning and growth as they shared their observations and wonders. Their insights filled me with hope. Finally, the depth I had been craving and had previously thought impossible, was unfolding right before my eyes.

Over the course of several days, we looked at different images of children. I projected one picture at a time onto the board and recorded what my students noticed and wondered about the kids in the photos. These observations and questions led to some really meaningful discussions about important things, including race, gender, ability, and diversity, and we came to the conclusion that while our physical appearance can be an important part of our identity, it can’t tell our whole story. People can make assumptions about who we are and what we are capable of based on our physical characteristics. These assumptions can be false and hurtful, can make us feel “less than”, and can lead to different types of discrimination. We also concluded that there are so many important things that make up a person’s identity that are invisible – we can only “see” them if someone is comfortable sharing them with us. My students demonstrated so much learning and growth as they shared their observations and wonders. Their insights filled me with hope. Finally, the depth I had been craving and had previously thought impossible, was unfolding right before my eyes.

After only two months of exploring identity using the cognitive tools of IE, I interviewed my students about their learning:

“Identity is to know who somebody is. If you don’t know about identity, you won’t know about anything about any people or yourself.” – J.G.

“Identity is what you look like on the outside and what you are on the inside. It’s important to learn about identity so you can learn about yourself, and when you learn about yourself, you can learn other peoples’ identity.” – A.M.

“Learning about identity helps you get along with other people. If someone is different from you, it makes it funner to play with them because they are different.” – K.M.

We have only just begun our exploration of identity, but already the experience is different. By planning my teaching with an IE approach, and through the purposeful use of cognitive tools, I have been able to engage the emotions and imaginations of my students. The learning I have witnessed is more thoughtful, more meaningful, more connected, and more memorable. And at the end of the day – isn’t that what education is ultimately for?

References

Egan, K. (2002). Getting it wrong from the beginning: Our progressivist inheritance from Herbert Spencer, John Dewey, and Jean Piaget. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Egan, K., &, Judson, G. (2016). Imagination and the engaged learner: cognitive tools for the classroom. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Wagamese, R. (October 14, 1955-March 10, 2017) Ojibwe from Wabeseemoong Independent Nations, Canada

Great essay, thank you so much. It’s lovely to read how the students discovered the inclusive leadership skill of Connecting with Differences!

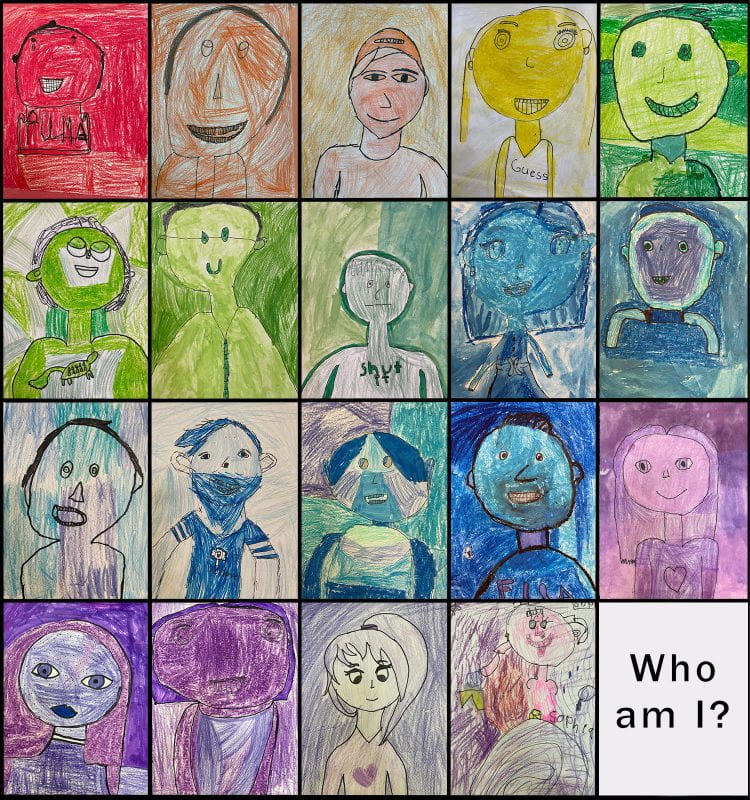

I’m curious about the portraits and the instructions for that exercise. Were the children taught about monochromatic pallet, or did you give parameters of choosing three colors next to each other on the color wheel… or???

Thanks so much for your kind comment. The self-portraits that the students made came with very simple directions. Each student chose a colour from the rainbow and we talked about only using shades of that colour in their portrait. The students drew their portrait with pencil first, fine-lined with sharpie and added the colour last. They had a choice of mediums – crayon, pencil crayon, felt or watercolours, and many students chose to use a combination of these. Using different mediums made it much easier to include different shades of the chosen colour. So simple and so beautiful!