By Dr. Kieran Egan

Who wrote the greatest work about education? Plato. Who has presented the richest vision of human possibility and described detailed steps to its achievement? Plato. Who has outlined the most complex developmental theory? Plato. Who was the first to offer an extensive and detailed argument for the equal education of women and men? Plato. Who includes the best jokes in a treatise on education? Plato. Who exemplifies educational ideas with the most powerful images and metaphors? Plato. Who has articulated the richest and most complex conception of human intelligence? Plato.

A.N. Whitehead suggested that all Western philosophy can be read as just a series of footnotes to Plato. Whitehead also pointed out that whatever field of philosophical inquiry we care to pursue, when we get to the furthest point our minds can comprehend we will see Plato coming back from somewhere far beyond. Plato’s educational ideas come to us with the dazzlement of brilliant images and stories and shrugs and winks. They are not exactly untroubling. In his Republic there be dragons.

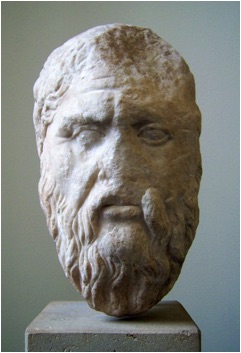

If you walk Unter den Linden from the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin you will come to the Pergamon Museum, in which you can see a Roman copy of an ancient Greek bust of Plato. Hard to tell, after the wear and tear of centuries, whether the lips are smiling or sneering or just relaxed in seriousness as he gazes beyond you.

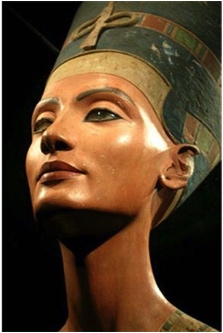

A short walk from the Pergamon, among that set of buildings that constitute one of the world’s greatest museums, you may find another mesmerizing head: that of Nefertiti. Her calm gaze and still features can’t hide the truth that she was not only more beautiful than anyone else but also cleverer. At least, what records we have suggest that’s how other people at the time saw her.

A short walk from the Pergamon, among that set of buildings that constitute one of the world’s greatest museums, you may find another mesmerizing head: that of Nefertiti. Her calm gaze and still features can’t hide the truth that she was not only more beautiful than anyone else but also cleverer. At least, what records we have suggest that’s how other people at the time saw her.

Some inconveniences of time and place, and predilections, mean Plato and Nefertiti couldn’t have become the ultimate power couple one might imagine: Plato pouring the wine and Nefertiti pulling the roast lamb out of the oven. A dinner party we might hope to be invited to in heaven perhaps. You might expect to hear sublime discussions of power and justice, but they’ll likely spend it bickering about who’s doing the washing up, which is, of course, a discourse on power and justice.

Mind you, that museum complex is full of stuff looted from other people. The only possible competitor is the British museum, which picked up some nice pieces too, including, of course, the Elgin Marbles, which the Greeks wistfully call the Parthenon Marbles, and which Plato would have seen when they were in their original colourful glory. The Greeks keep trying to negotiate with the Brits for the Marbles’ return. The Brit response is a diplomatic variant on: The channel is guarded by the Royal Navy, the skies are patrolled by the Royal Air Force, and, if required, the Mediterranean hides nuclear armed Trident submarines so “If ya want ‘em, come and get ‘em.”

I used to ask incoming Ph.D. students in Education about what they had read, and learned that hardly anyone was familiar with Plato’s Republic. Some knew about it, or had read more fashionable modern writers’ accounts of it and what was wrong with it, or intended to read it, or had read the equivalent of a Coles Notes, or SparkNotes, version. But most had only some vague sense of Plato being the ultimate “traditionalist,” or in more modern terms the archetypal logocentric patriarch.

That is, most people in education today read much more limited works and few read and re-read Plato’s great work with close attention. I know that many people buy the book, and you will find it, still crisp after many years on bookshelves. Caves and Philosopher Kings, Divided Lines and the Just Society, and other vague memories and echoes are evoked by a mention of Plato. But maybe at breakfast the morning after that dinner party with Plato, Nefertiti would be discussing intricate details of the million ideas kicked into flight by that greatest educational text.

What does it say about a field in which by far the greatest text, and the questions and answers it proposes, are largely ignored in favour of parochial concerns? Those parochial concerns can be made sense of only in the larger context of meanings about the nature of education. And that context, an inquiry that Plato largely created and shaped for us, has largely slipped from our minds. The ideas are still there for the taking.

If ya want ‘em, go and get ‘em.

Story, Writing, Education, maybe a distant relation of Alfred North Whitehead looking for an educational key that involves story. Many people devoutly follow one book so I am now going to study Plato’s Republic-Once upon a time I read Winnie the Pooh in Latin-and try to link it to praxis and heutagogy in Primary Education

Hi Tom–your connections to Winnie The Pooh sounds interesting! Enjoy the Republic. Always good to have an educational book on the go–and in this case one that challenges the brain!