By Glenn Ellis (Professor of Engineering, Smith College, USA)

The year is 1981 and it is the first day of my geotechnical engineering class. The professor enters the classroom and writes on the board:

geotech—the dark arts of engineering!

We were fascinated and eager to learn all about this magical topic. However, the magic quickly dissipated as the class soon began to feel just like any other class. Sadly, the spell was broken!

Dr. Kieran Egan (2004) tells us that a starting place for Imaginative Education is to consider what is emotionally engaging about the topic. For geotechs the answer is often that soil is so much more complicated than steel, concrete or many other materials that the field requires a completely different way of thinking (hence the “dark arts” reference).

Geotechs love the challenges and mysteries that are inherent to the field. They have even developed their own set of heroes and heroines and relish their connection to them.

Decades have passed and now I’m teaching geotech at Smith College. In this blog, I will share how I have used a range of cognitive tools in my teaching to engage imagination and tap into the emotional engagement that connects geotechs to their field.

Mythic Understanding

Undergraduates have long passed the age when Mythic Understanding dominates how they engage with the world around them. (If you are new to Imaginative Education, here is a post describing the concept of “Kinds of Understanding”.) However, the cognitive tools associated with it and with our body’s engagement in the world do not go away. Instead they are transformed and become part of later understandings (Egan, 2004). For example, I use fantasy, mystery, humor and narrative cognitive tools in my course by treating each student as a witch or wizard taking a “dark arts” class at Hogwarts. The fantasy begins with a sorting hat placing students into different “houses” within the geotech field. This process helps them to connect emotionally with geotech since each house has its own history, unique contributions to the field, and numerous heroes and heroines.

Throughout my course the dark arts narrative is revisited regularly. For example, students are introduced to liquefaction by learning a “spell” in which they tap a beaker containing a Harry Potter figure standing on solid ordinary sand. Within seconds Harry starts sinking into quicksand and students begin the task of unravelling the mystery of how the spell works.

Romantic Understanding

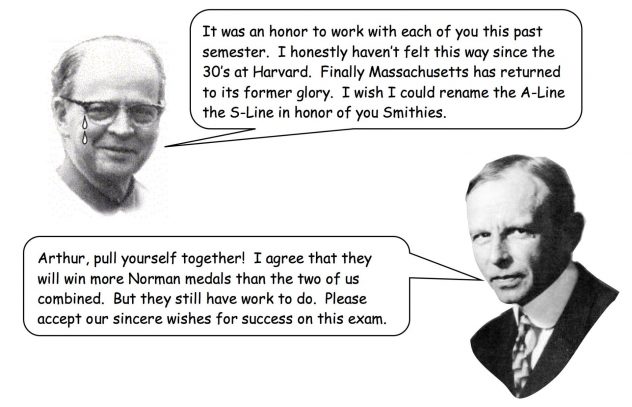

Association with heroes is a Romantic cognitive tool that I use. (Clear here for more information on the Romantic Kind of Understanding.) Progress in understanding soil behavior was slow until well into the 20th century and the arrival of Karl Terzaghi and Arthur Casagrande. Both play prominent roles in my class. New topics are introduced through anecdotes about their heroic actions. (For example, when the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) moved to Cambridge in 1916, buildings began sinking at an alarming rate into the soft soil. Fortunately Terzaghi joined MIT and saved the campus (Fatherree, 2006).) Their pictures with dialogue appear everywhere throughout the course and provide encouragement and historical insights to students. (See also humanization of meaning.)

Another Romantic cognitive tool I use with my geotech students exploring the extremes of experience and the limits of reality. For example, quicksand is normally only explored briefly in geotech classes to illustrate how stress and seepage theories can be applied. I reverse this and make quicksand the context and motivation for learning about stress and seepage. The unit begins with the dark arts spell described earlier and unfolds through narratives including real accounts of being caught in life-threatening quick conditions in a cofferdam and during an earthquake. The unit ends with students going on a virtual safari based upon recorded encounters with quicksand. During the safari they need to apply their collective understanding to save students who fall into quicksand under a variety of scenarios. The safari ends with a lab in which students get to see, feel, measure and play with real quicksand.

Philosophic and Ironic Understandings

With a Philosophic kind of understanding of the world, students search for authority and truth and develop a more systematic comprehension of the world around them. I engage students in Philosophic understanding by using theoretic narratives and concept maps to help them see the big picture and organize their knowledge productively. Initially these items are teacher-generated, but gradually the responsibility shifts to the students.

In Ironic understanding students come to recognize the inadequacy of Philosophic understanding to fully explain the complex behavior of the world. My students’ sense of irony is engaged in my class when they try to understand why geotechnical engineering is called the dark arts. Throughout the course their understanding grows as they engage with the inadequacy of current theories and methodologies to fully explain soil behavior. For example, in one homework assignment, students are asked to brainstorm new soil tests that improve the current practice.

Were Students Engaged?

An independent evaluator assessed the impact of Imaginative Education in my geotech class. She found that all students agreed that both the dark arts and the Terzaghi/Casagrande narratives were engaging. Also, all student responses to open-ended questions were positive. Example responses include:

“I feel special learning geotech because I feel like I kind of get to “talk” to Terzaghi and Casagrande during the learning of this course. They inspire my study at some point.”

“My attention was always kept. I loved starting each class with some sort of Harry Potter anecdote and finding the hidden KVT [Terzaghi] references in our handouts.”

It is interesting that two students wrote that the dark arts narrative was “kind of silly” and “completely ridiculous,” but then continued to say that it “helped me relate to the topic better” and “I loved every minute of it.” This supports the idea that even when students are past one kind of understanding, the tools associated with it are transformed and remain in their current understanding. As one student reported,

“We may be college students, but we still love to have some imagination time.”

Learn More

A more detailed account of my geotech class can be found here. My research team’s attempt to create an imaginative online learning environment for middle school engineering can be found here.

References

- K. Egan, An Imaginative Approach to Teaching, Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA, 2004.

- B.H. Fatherree, The History of Geotechnical Engineering at the Waterways Experiment Station 1932-2000, U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center, U.S., 2006.

About The Author

Glenn Ellis is a Professor of Engineering at Smith College who teaches courses in engineering science and methods for teaching science and engineering. He received a B.S. in Civil Engineering from Lehigh University and an M.A. and Ph.D. in Civil Engineering and Operations Research from Princeton University. The winner of numerous teaching and research awards, Dr. Ellis received the U.S. Professor of the Year Award for Baccalaureate Colleges from the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and the Council for Advancement and Support of Education. His research focuses on creating K-16 learning environments that support the growth of learners’ imaginations and their capacity for engaging in collaborative knowledge work.

Glenn Ellis is a Professor of Engineering at Smith College who teaches courses in engineering science and methods for teaching science and engineering. He received a B.S. in Civil Engineering from Lehigh University and an M.A. and Ph.D. in Civil Engineering and Operations Research from Princeton University. The winner of numerous teaching and research awards, Dr. Ellis received the U.S. Professor of the Year Award for Baccalaureate Colleges from the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and the Council for Advancement and Support of Education. His research focuses on creating K-16 learning environments that support the growth of learners’ imaginations and their capacity for engaging in collaborative knowledge work.