The last two days I attended and presented at the 9th Annual World Environmental Education Conference (#WEEC2017) in Vancouver, B.C. I want to write about one session that I found incredibly engaging–it left me feeling inspired and curious.

The session was entitled Weaving Conversation Circles for New Understandings. Sharon Kallis and Rebecca Graham facilitated the workshop. Now, I am not a knitter nor would I identify myself as any other kind of fiber artist—let alone an artist. I chose the session because it was described as a “novel format”. They had me at “novel”.

This post describes that novel format, how we processed stinging nettle for weaving, and what issues/topics of discussion emerged within our group as we collaboratively worked and learned.

A Novel Format

Sharon and Rebecca began by situating themselves and their practice. It was the first I had heard of the EartHand Gleaners society. I was immediately intrigued by the notion of “gleaning”—being creators and producers of art and other materials without first being consumers. We learned that they work with foraged fibers. They both expressed a love of the local, a love of using their hands, and a desire to re-wild urban environments.

Sharon and Rebecca began by situating themselves and their practice. It was the first I had heard of the EartHand Gleaners society. I was immediately intrigued by the notion of “gleaning”—being creators and producers of art and other materials without first being consumers. We learned that they work with foraged fibers. They both expressed a love of the local, a love of using their hands, and a desire to re-wild urban environments.

Sharon and Rebecca conduct “weaving” workshops—and workshops that “weave” pedagogical ideas. In their workshops dialogue and “doing” are warp and weft. What they call the “conversation circle” is not as it may seem. It is a practice that involves more than talking. They facilitate conversation while participants are using their hands. Before we started to do and to talk, they suggested that the format creates a sense of calm and opennes within a group. Silences are comfortable. People are at ease talking as they are physically engaged in a tactile activity.

“When people’s hands are busy, incredible conversations can happen” (Sharon Kallis)

This is, indeed, what we experienced as we learned to process the stinging nettle.

Some questions our hosts encouraged us to explore as we worked had to do with foraging as part of ecological practice with children but also with our families/in our lives:

How do we sustainably forage in urban environments? How do we forage with respect for indigenous communities who live on the land? How do we forage with respect for other beings (human and animal) that might rely on the plants? What do we forage? Who forages? How much is appropriate to take?

The Work: Processing The Nettle

We started by selecting a piece of stinging nettle. Sharon and Rebecca brought a selection for us to choose from. They harvested it ahead of time and now, kept it under damp canvas in order to preserve it in the air-conditionned room.

First we cracked the “nodes” in the nettle. This was finger or foot work. The aim was to soften the nettle.

Next we began pulling the pith (woody part) off the fiber (soft part). We discovered that making small cracks in the nettle made it easier to peel off the pith, leaving behind the soft strands of the fiber.

And so we all cracked nodes and pulled the pith from our pieces of stinging nettle—all working together in processing nettle into long strands that would later be used for creating a fishing net.

I learned that stinging nettle is easy to process and the act of doing it, in conversation with colleagues, is soothing.

I learned about Daylily. This is a picture of some rope made from Daylily—my teachers told me that this is a plant that can be easily worked by children. (They mentioned that it is also possible—despite those thorns—to harvest and process Himalayan Blackberry with children.)

The Talk: Some Themes

Our discussion crisscrossed a range of topics, from the notion of “ownership” and problems with that concept in relation to land, to the idea of “responsibility” and “giving back”.

GIVING THANKS. How do we “reciprocate” with the land? How do we give thanks to the land? To the plants? I love the idea of giving thanks and the many ways we can authentically do that—remembering, of course, that we owe that to the plant species who share our communities with us. I learned a lot from the outdoor and indigenous teachers in the session. One idea that I plan to employ immediately is very simple: Say “thank you” in the language of the land. That is, use the language of the first people’s on whose land you are residing and say thank you in that language. Acknowledge our roots.

(This means “I Thank You” in the Halq’eméylem language, the language of the Indigenous people from my community). (Source: First Voices)

Other ideas involved a physical touching of the land in gratitude and respect. Ultimately, our biggest educational challenge is changing our relationship with nature—so it is important to think about “reciprocity” or how to “give thanks” as part of our ecological practices in our community.

FORAGING. What can we forage? Answer: All kinds of things (flowers, berries, leaves, nuts, roots etc.) And, what can children learn from the foraging? Answer: Processes of regeneration, decomposition, harvesting/processing, life cycles! With weaving in mind, what plants appear to you in your place? What else can children forage? Seek the affordances for foraging in your Place—rural, urban, suburban. Context doesn’t really matter. Our communities are rich with materials.

A “novel format” indeed! And an inspiring one. In the end I have inspiration for my teaching and I have new knowledge and respect for ecological practices we can employ as imaginative Ecological educators.

Find Out More

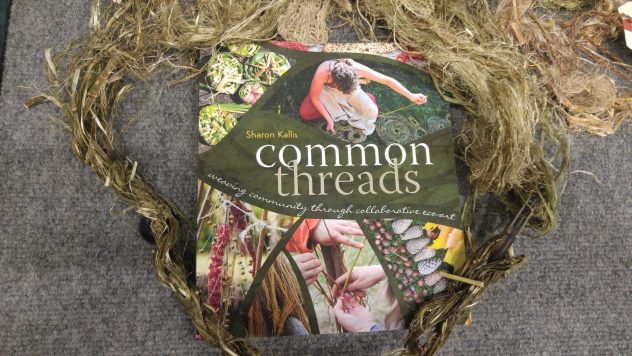

By Sharon Kallis: Common Threads: Weaving Community Through Collaborative EcoArt

More information on FORAGING: Cultural Transmission at Nature Kindergarten: Foraging As A Key Ingredient (By Clare Nugent & Simon Beames, 2015) **The article looks at foraging in the context of two different nature-based kindergartens and how the practice is mediated/influenced by influential adults working in these programs. (pp. 78-91; Canadian Journal of Environmental Education (Volume 20/2015).)