By Rebecca Thomas (Lecturer, University of East Anglia)

By Rebecca Thomas (Lecturer, University of East Anglia)

Playful Learning 18, held at Manchester Metropolitan University (UK) in July 2018, was a concatenation of talks, workshops, gatherings and games, involving some 200 people, attending over forty sessions spread over two and a half days. The point of the gathering was to introduce and develop a variety of aspects of play, problem solving and participation, with a special focus on digital gaming, role play and processes of making. Among the many interesting session themes were digital and video game design, puzzle creation in relation to curriculum development, spatial negotiation, the development of open resources, curiosity-related object-making, and issues of copyright and licensing.

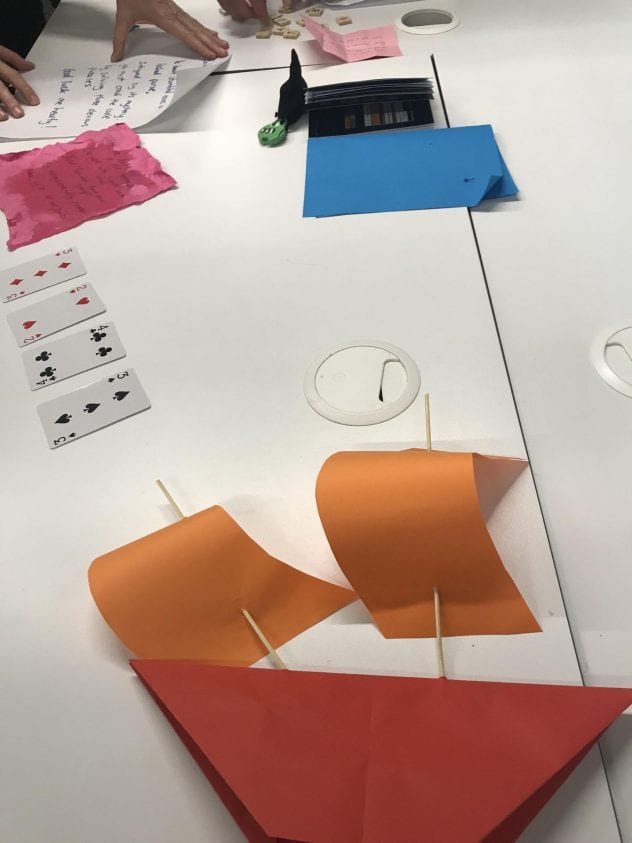

Running throughout the entire conference was the theme of pirates, a constant backdrop which manifested itself in numerous instances of role-play, dressing-up (and dressing-down!), especially for the mid-conference pirate banquet.  This theme allowed the participants to indulge in various aspects of the pirate’s imaginative environment, touching upon issues such as subversion, decipherment, buried treasure, conflict and crewmanship and other related matters, all enabling a sideways-glance at the state of educational issues in the UK today. This did not necessarily mean that the participants were press-ganged into doing things they didn’t want to do, the playful, open atmosphere of the conference being in fact an attractive feature of the whole event.

This theme allowed the participants to indulge in various aspects of the pirate’s imaginative environment, touching upon issues such as subversion, decipherment, buried treasure, conflict and crewmanship and other related matters, all enabling a sideways-glance at the state of educational issues in the UK today. This did not necessarily mean that the participants were press-ganged into doing things they didn’t want to do, the playful, open atmosphere of the conference being in fact an attractive feature of the whole event.

Using games and play as a means for the development of educational strategies is a relatively new procedure, one perhaps on the increase in these times of metric-driven institutions, as a deliberate countering of such a reductive approach. As Nicola Whitton (2018) has noted in her article Playful learning: tools, techniques and tactics,

“…as an emerging field, playful learning in higher education lacks a robust foundation; there is a dearth of research evidence as to its applicability and effectiveness, and a lack of understanding of the underpinning mechanisms that support the hypothesised links between play and learning, creativity and innovation.” (p. 2)

However, Whitton herself is a pioneer in this field and it would seem that the evidence is mounting that utilising play in this way at least helps to retain certain important characteristics that the model of the university as “performative” enterprise has steadily destroyed: creativity and curiosity, the exploration of ideas, active and collaborative engagement, and, not to be forgotten or neglected, pleasure and fun.  Whitton proposes that with play being increasingly brought into education one very visible change is the development of what she calls “the Playful Learning Conference, which is an attempt to rethink the conference format playfully.” Playful Learning 18 is a perfect example of this novel approach to conference construction, in which participation, dialogue and game-playing result in a crossing of boundaries between what would conventionally be speakers and audience, “active” and “passive” roles in which a strong hierarchical format is maintained.

Whitton proposes that with play being increasingly brought into education one very visible change is the development of what she calls “the Playful Learning Conference, which is an attempt to rethink the conference format playfully.” Playful Learning 18 is a perfect example of this novel approach to conference construction, in which participation, dialogue and game-playing result in a crossing of boundaries between what would conventionally be speakers and audience, “active” and “passive” roles in which a strong hierarchical format is maintained.

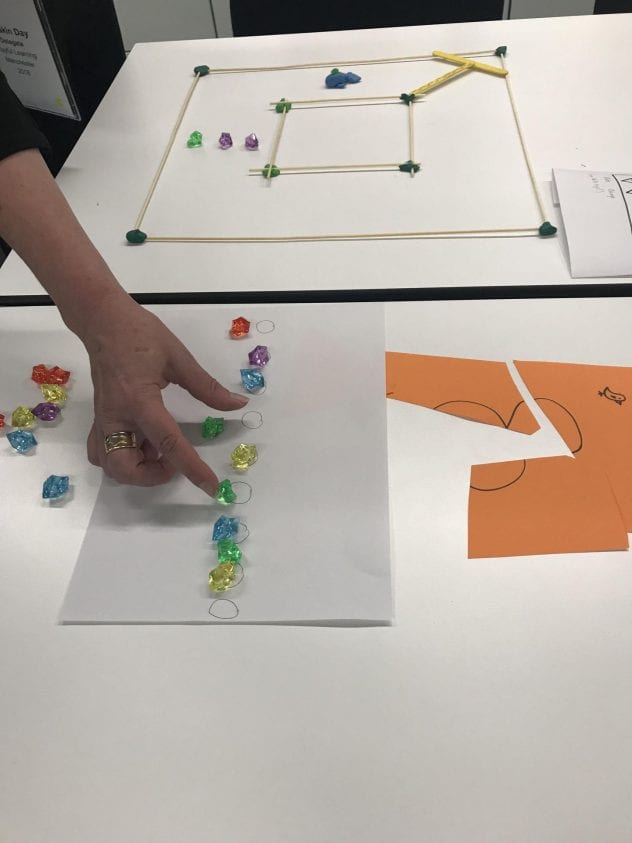

Testing out ideas and processes of collaboration is one of the functions of role-playing, and there were plenty of opportunities in Manchester to work in ways beyond or outside conventional behavior patterns. Although a large number of the workshops involved aspects of digital gaming, there were many sessions in which the physical construction of games or other thought-provoking objects was carried out. Several of the sessions I attended seemed to have just the right mix of physical and cognitive procedures and concerns, being broad enough to involve people with little experience of the specific discipline involved whilst still retaining a strong connection to issues particular to that field.

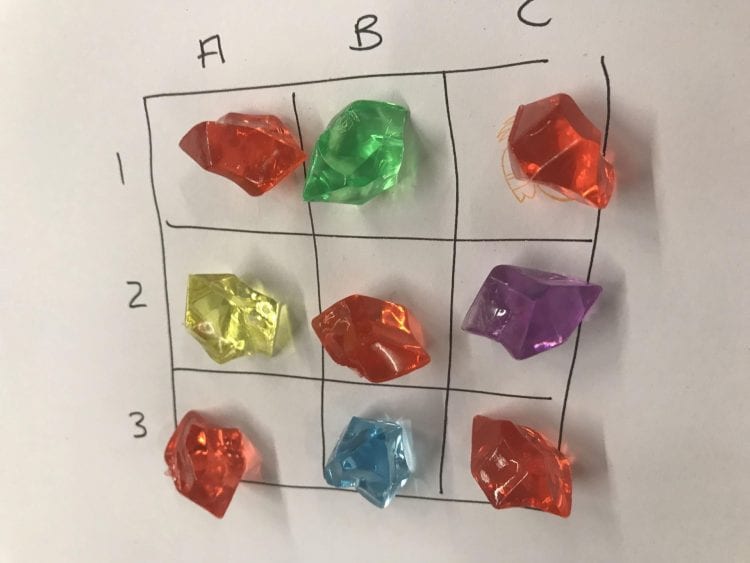

For example, in “Puzzle Jam”, organised by Matthew Crossely, the group’s challenge was to design a puzzle inspired by the idea of finding buried treasure. A lock had to be cracked, a map deciphered, a treasure ultimately unearthed. Four teams, each with four or five members brainstormed, setting up a puzzle which one of the other groups had to decode.  This was highly stimulating, providing a clear model of an engaging experience which could be easily adapted for use with our own students. Working together in this way, insights into how we could ourselves design other useful and provocative puzzles were gained.

This was highly stimulating, providing a clear model of an engaging experience which could be easily adapted for use with our own students. Working together in this way, insights into how we could ourselves design other useful and provocative puzzles were gained.

An important question implicitly raised by this conference was the role of play within pedagogy, its function and value as an educational strategy, but also how such an important approach might be introduced into educational institutions as an uncontroversial aspect of the curriculum, rather than as a kind of guerrilla strategy or quirky one-off event. Surely such an act would help to inject fun and energy into an increasingly conformist educational system which is sorely in need of such an inspirational approach.

Whitton, N. (2018). Playful learning: tools, techniques, and tactics in Research in Learning Technology, 26, p. 2.

For more information see http://conference.playthinklearn.net/blog/

About The Author

Rebecca Thomas is a lecturer in the MA in Higher Education Practice program at the University of East Anglia, and was formerly Programme Leader of Photography, and Teaching and Learning coordinator in the School of Creative Arts at the University of Hertfordshire. Rebecca’s current interests include the development of curiosity through integrated teaching structures, developing disciplinary pedagogies and the creation of teaching resources. She is also a visual artist.

What a great round up of the conference, Rebecca! I much enjoyed being in your pirate gang for the puzzle jam.