By Kate Charette (Educator & PhD Candidate, University of New Brunswick)

By Kate Charette (Educator & PhD Candidate, University of New Brunswick)

I first learned about Imaginative Education (IE) as an elementary school teacher doing my Masters degree. In the evenings after teaching my kindergarteners I would read about engaging students’ imaginations by shaping the curriculum as an exciting story much like a journalist would, rather than thinking of it as a checklist to cover. I would explore ideas about what cognitive tools my students were using to understand the world around them, and how to frame my lessons using these tools to make an exciting, interesting story. It was the first time I was encouraged to think about shaping instruction around what students are already good at as opposed to thinking of them as having deficits that need to be corrected.

IE in Elementary School History Teaching

IE gave me the language I needed to advocate for the kind of history work I knew my students could do even in the early years. For all learners, but particularly in K-2, oral language tools offer a way to engage with history that is essential when students are emerging (or struggling) readers and cannot access written texts. It creates space for students to use skills and abilities that can often get left behind in text-heavy study. Barton and Levstik’s (2011) description of “talking historically,” with young students is a wonderful way to frame historical inquiry in the elementary classroom where learners can deepen their historical skills and knowledge while drawing on ways of understanding the world already familiar to them: story, metaphor, role play, etc.

(For further discussion of imagination and history in the elementary classroom see the following blog post for The History Education network: “Talking Historically”: Using Performance to Develop Young Students’ Historical Thinking

While Peter Seixas’ “Big Six” wasn’t conceived for elementary history educators, the six historical thinking concepts offer an excellent framework for teaching and assessing student thinking overall. Research from Keith Barton and Linda Levstik (2011), Hilary Cooper (2012), and Anne-Lise Halvorsen (2012) (among others) helps to fill in what we know about our youngest learners when it comes to history. Imagination isn’t often explicitly discussed by historical thinking researchers, but the tools of the imagination feature prominently in their recommendations for engaging young learners in historical study.

The Timeline as a Story Form

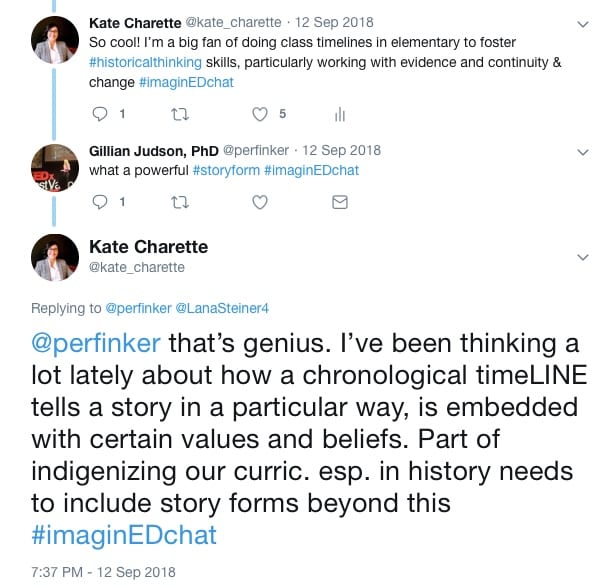

My recent interest has been in doing work with timelines to support K-2 development in the historical thinking concept of continuity and change, but it wasn’t until an #imaginEDchat on Twitter that I thought about how the timeline shapes our understanding of history in ways that can be problematic. The timeline is a linear, chronological representation of the passage of time whose very form is embedded with certain values and beliefs about how knowledge is recorded and presented, what events matter, and how time itself works. It differs significantly from a cyclical or seasonal view of the passage of time, and while I have thought of it as the primary way to teach students about recording events over times, I am learning to shift my perspective.

The timeline is a story form that tells a story in a particular way, and precludes the possibility of telling that story in other ways. It is especially important to keep this in mind as we are concerned with pedagogy for reconciliation, and creating space within the curriculum for Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives to co-exist. IE offers us a way of thinking about how the forms we use to teach are not just tools, but ways of shaping information that are already storied. This prompts us to consider which stories we are telling and which knowledges we are privileging in the classroom perhaps without realizing it.

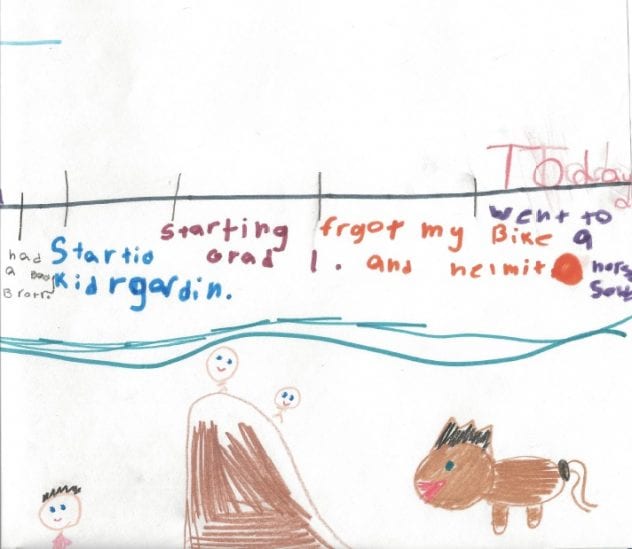

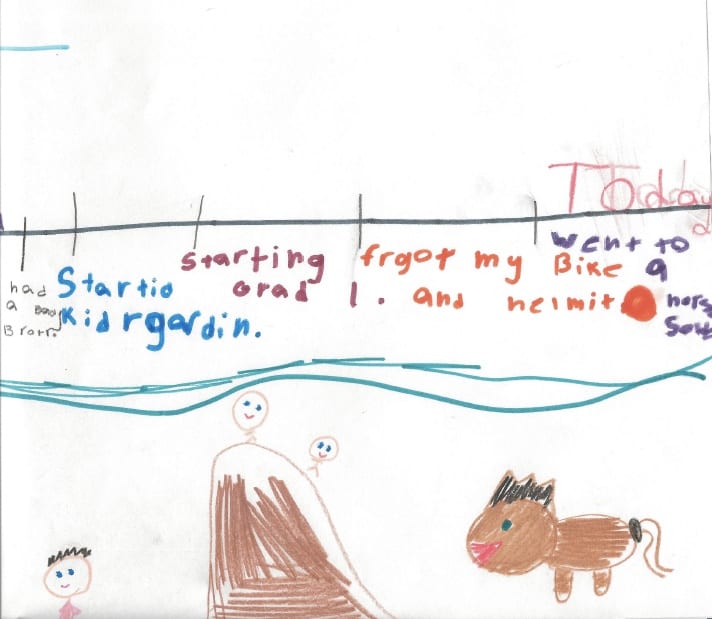

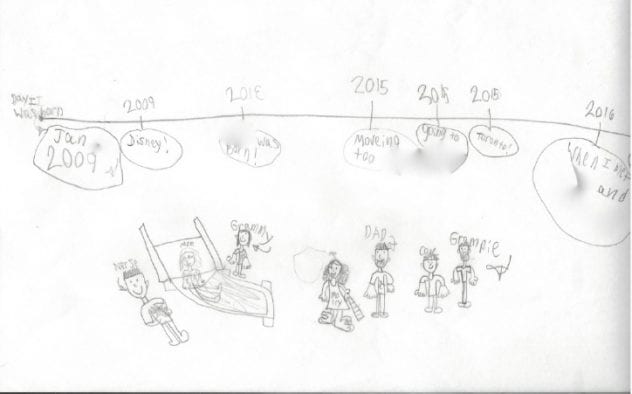

Personal and classroom timelines are an excellent way for young students to explore continuity and change, as well as address the concept of significance and to practice collecting evidence to support arguments and make claims. But they cannot be only way we teach how the passage of time and events are recorded, and we need to be mindful of how much space these forms take up in our teaching. Understanding how knowledge about the passage of time is recorded in a cyclical or seasonal model, what events feature and why, and what this story form teaches through how it shapes information, should also become an integral part of how we do history with elementary students.

Personal and classroom timelines are an excellent way for young students to explore continuity and change, as well as address the concept of significance and to practice collecting evidence to support arguments and make claims. But they cannot be only way we teach how the passage of time and events are recorded, and we need to be mindful of how much space these forms take up in our teaching. Understanding how knowledge about the passage of time is recorded in a cyclical or seasonal model, what events feature and why, and what this story form teaches through how it shapes information, should also become an integral part of how we do history with elementary students.

References

Barton, K., & Levstik, L. (2011). Doing history: investigating with children in elementary and middle schools (4thed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Brophy, J., Alleman, J., Halvorsen, A-L. (2012). Powerful social studies for elementary students (3rded.). Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

Cooper, H. (2012). History 5-11: a guide for teachers (2nded.). New York, NY: Routledge.

As parents who spend more time with their children, how can they develop their children’s talents by story telling?

I would recommend that you use these tools of engagement –they engage and grow imagination! http://gillianjudson.edublogs.org/tips-for-imaginative-educators/ You can also take those imaginative inquiry questions outside in explorations: http://gillianjudson.edublogs.org/walking-curriculum-imaginative-ecological-learning-activities/