By Courtney Robertson (Vice-Principal, MEd in Imaginative Education)

By Courtney Robertson (Vice-Principal, MEd in Imaginative Education)

The role of being an administrative leader often feels like a complicated and impossible juggling act. Trying to keep all the different pieces “in the air” (e.g. functioning at the optimum level) can be a great challenge for even the most experienced leader. We envision supporting classrooms, teachers, and practice, in a way that drives the school community forward in positive ways, and yet we can hit road block after road block–obstacles that can destroy the utopian dream we have for our schools.

What becomes of great importance, then, is how we use our valuable, limited time with our staff. How we use our time to effectively support and guide practice and develop positive learning culture in our buildings.

So are we missing an important way to engage and learn with and from our staff? I think perhaps we are, and those who understand and value the role of imagination in all areas of education, including LEADERSHIP, want to shift that lens.

As leaders, how do we maximize imagination in the culture, management, and success of our schools?

First we need to define imagination. This is a main goal of the Centre for Imagination in Research, Culture and Education (or CIRCE) at Simon Fraser University.

Imagination Misunderstood

How do we address misconceptions of imagination?

I remember being asked in my first MEd course, who I believed to be more imaginative, children or adults. Of course I immediately went to my background as a Kindergarten teacher and staunchly said, “CHILDREN! You should see them when they play! They create, and use voices, and become different characters that fit their story line. They use their imaginations like crazy!”

Now, graduate study is an interesting thing. You typically choose a program because you know a lot (Or you think you do!). You have taught for several years, and you feel confident that you know your stuff. So you expect to do really well in graduate studies, right? This should be a walk in the park! Well, if you are lucky enough to be really challenged (and if you are willing to be changed) what ends up happening is a complete dismantling of yourself. Of your thinking. Your knowledge. And your certainty. And while that seems awful, you can come out the other side with a new awareness of your own preconceptions, presuppositions, and an understanding of how important it is to question and reflect. So back to that first question that rocked my world: Who was more imaginative, children or adults?

We had a lively debate in that class. Through the discussion, many of us realized that we didn’t have a firm definition of imagination. Rather we had a preconceived notion that it involved a child being able to pretend to be an astronaut, or a mommy/daddy taking care of a baby in the dramatic play area.

I believe we need to understand imagination if we are to fully appreciate its importance in educational leadership.

So how do we define it? As a society we have generally defined imagination as the following: (retrieved from dictionary.com)

imagination

[ih-maj-uh-ney-shuh n]

noun

- the faculty of imagining, or of forming mental images or concepts of what is not actually present to the senses.

- the action or process of forming such images or concepts.

- the faculty of producing ideal creations consistent with reality, as in literature, as distinct from the power of creating illustrative or decorative imagery.

- the product of imagining; a conception or mental creation, often a baseless or fanciful one.

- ability to face and resolve difficulties; resourcefulness: a job that requires imagination.

- Psychology, the power of reproducing images stored in the memory under the suggestion of associated images (reproductive imagination) or of recombining former experiences in the creation of new images directed at a specific goal or aiding in the solution of problems. (creative imagination).

What I find most interesting about this definition is that for many, imagination is understood as baseless or fanciful! This is the misconception that Imaginative Education–and all those Imaginative Educators out there–rail against. How can we shift the mindset of those that believe it is “fanciful” or “baseless”? The exact opposite is true of imagination; our world exists because of imagination! Inventions, solutions, and creations did not just appear because of a baseless or fanciful thought. Rather, careful, knowledgeable, and informed imaginative thought guides these brilliant thinkers to first imagine and then enact their ideas, dreams, and creations. So what we need to do is go back to the definition and unpack it further.

Psychology . the power of reproducing images stored in the memory under the suggestion of associated images (reproductive imagination) or of recombining former experiences in the creation of new images directed at a specific goal or aiding in the solution of problems (creative imagination).

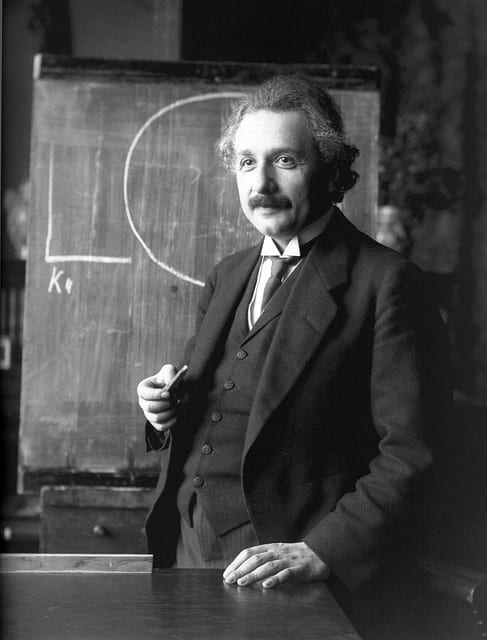

Let’s start understanding imagination here. This definition communicates the importance of knowledge as an influence to, and on, imagination. We need to know a lot of stuff, in order to think up new stuff! Einstein had an immense wealth of knowledge–it was this knowledge that convinced him that something he could not yet make sense of, or see, was there. Likewise, Nikola Tesla had an expert understanding of electrical currency and knew that there was a lack of efficiency in the circuit patterns that were used in early electricity models, therefore leading him to design a revolutionary way of thinking about electricity.

Let’s start understanding imagination here. This definition communicates the importance of knowledge as an influence to, and on, imagination. We need to know a lot of stuff, in order to think up new stuff! Einstein had an immense wealth of knowledge–it was this knowledge that convinced him that something he could not yet make sense of, or see, was there. Likewise, Nikola Tesla had an expert understanding of electrical currency and knew that there was a lack of efficiency in the circuit patterns that were used in early electricity models, therefore leading him to design a revolutionary way of thinking about electricity.

These examples tell us that in order to be imaginative, we need to know a lot about something. So how does this translate to leadership? Well, we have to be experts. We have to know a lot of things! But more than that, we have to know a lot about people, and what their story is, in order to efficiently support their practice. If our focus is improving reading instruction within our classrooms, then we as educational leaders, need to become experts in literacy, and likewise, need to help our teachers become experts. The more knowledge that our school community has, the more fuel our imaginations have to envision possibilities in our practice. We are more equipped to transform our practices.

Imagination is also steeped in emotion. Imaginative leadership requires us to seek out the emotional significance, or affective meaning, of learning, teaching, and leading. What do the stories in our building (of the learning, of the goals, etc.) tell us? How do they engage us emotionally? In Imaginative education we talk about the story-form as the chief way to engage learners. If we find the story of a topic, then that lends itself to engaging imaginative thought and therefore…MEANING.

Imaginative leaders create space for that emotional connection to subject matter, tasks, and learning. Imaginative leaders know that their teachers–all humans–perfink. We PERCEIVE. FEEL and THINK simultaneously. (Dr. David Krech) (Dr. Gillian Judson’s Tedtalk)–our emotions are at the core. We need to create opportunities to tap into our teachers’ and learners’ perfinking skills! And how do we do that? We use the cognitive tools that all learners have. (Check out this post to see how Gillian Judson employs cognitive tools in the leadership context specifically.)

Imaginative leaders think about how to employ cognitive tools such as mental imagery, or change of context (check out this list), to guide their teachers’ practice and unleash their imaginations. What would that look like in a staff meeting? How can you employ a cognitive tool to discuss and learn more about different issues or school topics? About the curriculum?

I believe that the goal of imagination is to move forward. To create more. To think more. To imagine more. This aligns with the vision of an educational leader. We are all passionate teachers who wanted to do more, and therefore chose administration as the path. While the realities of our work may become busy with messy cleanups, discipline, and management tasks that take far too long sometimes, we all have to remember why we moved into leadership roles. As cliché as it sounds, I believe that we all imagine the possibilities of what can be done as educational leaders. And that, my esteemed colleagues, is a great place to start the story of your leadership.

About The Author

Courtney Robertson is a Vice-Principal in Langley, British Columbia. She completed her Graduate studies with a focus in Imaginative Education at Simon Fraser University. Courtney began her career as an Early Learning Specialist and has continued to find passion and enjoyment in teaching and working with young learners. Her primary research areas include dialogical thinking and multiculturalism, the power of a beautiful narrative, and the “wonder” of teaching and learning for all students. You can follow Courtney on Twitter @wonderanded.

Join @CIRCE_SFU on Twitter to continue the conversation imaginative leadership conversation (#ILLG = Imaginative Leadership Learning Group). Join the CIRCE email list here and a get a free Imaginative Education starter kit.)