By Al Rudnitsky (Professor of Education & Child Study, Smith College)

By Al Rudnitsky (Professor of Education & Child Study, Smith College)

The speed at which many children’s informal knowledge of mathematics becomes separated from the more formal math they encounter in school is a challenge for math educators. As Jo Boaler says (2008), “Over time school children realize that when you enter Mathsland you leave common sense at the door.” Too many children in schools stop “making sense” of math and end up telling themselves they are not math people, they are just not good at it. Sadly, this message can readily become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

By creating a context children can relate to, word problems can be a powerful tool for connecting formal and informal knowledge. Unfortunately, the word problems found in most math curricula do not fulfill this promise. They are short – often three liners, about arbitrary things, done by unknown people, and appear at the end of instruction; making it entirely clear what operation is needed to produce an answer.

What might learners be able to do, if problems helped them imagine themselves as agents and actors in situations where interesting math problems arise?

Enter Imaginative Education (IE).

Kieran Egan’s ideas about imagination and how imagination enhances and supports learners as they develop mastery of the tools and knowledge that comprise human culture have been central to my thinking as an educator and a learner. I find story (or narrative, or metanarrative) the most essential of the “cognitive tools.” Story creates the context through which other cognitive tools become meaningful. Why not embed math problems in stories that make sense to children, with characters they come to know and maybe even care about?

Learning Math Through Stories: Introduction

The Math Stories were created at Smith College. They take place at a farm stand and on a farm. The main characters include:

- Sophie who is observant, open-minded, thoughtful, a good listener and someone who shares ideas in an inclusive way.

- Norman who is sometimes too sure about things but is willing to think about new ideas and revise his thinking.

- The characters of Sophie and Norman emerged from the work of Gina Cowley, a first grade teacher. She was an early Imaginative Education explorer and created rich narratives to convey complicated ideas. The ideas were often embodied in individual roles (e.g., a poet, a chemist, a change agent). We had talked about Imaginative Education in anticipation of a conference at which Kieran Egan was the keynote speaker.

- Ezra who is co-owner of the farm stand and someone who is constantly challenged by the mathematical situations he finds himself in.

- Irma who is co-owner of the farm stand who often offers practical suggestions to the others.

- Amara and Ben, the farmers.

In “Eggs Come in Three Colors,” Amara is filling egg orders. There are three kinds of eggs. The story includes many details about chickens and eggs. The math problems first require finding the total number of eggs in an order with three things to add (addends). Then orders come in with a total but missing one of the egg varieties (an unknown addend). Finally order slips fall into a puddle obscuring two of the items in the order, creating problems that have multiple and uncertain solutions. This is challenging math and learners must develop a mental model that helps them represent the problem.

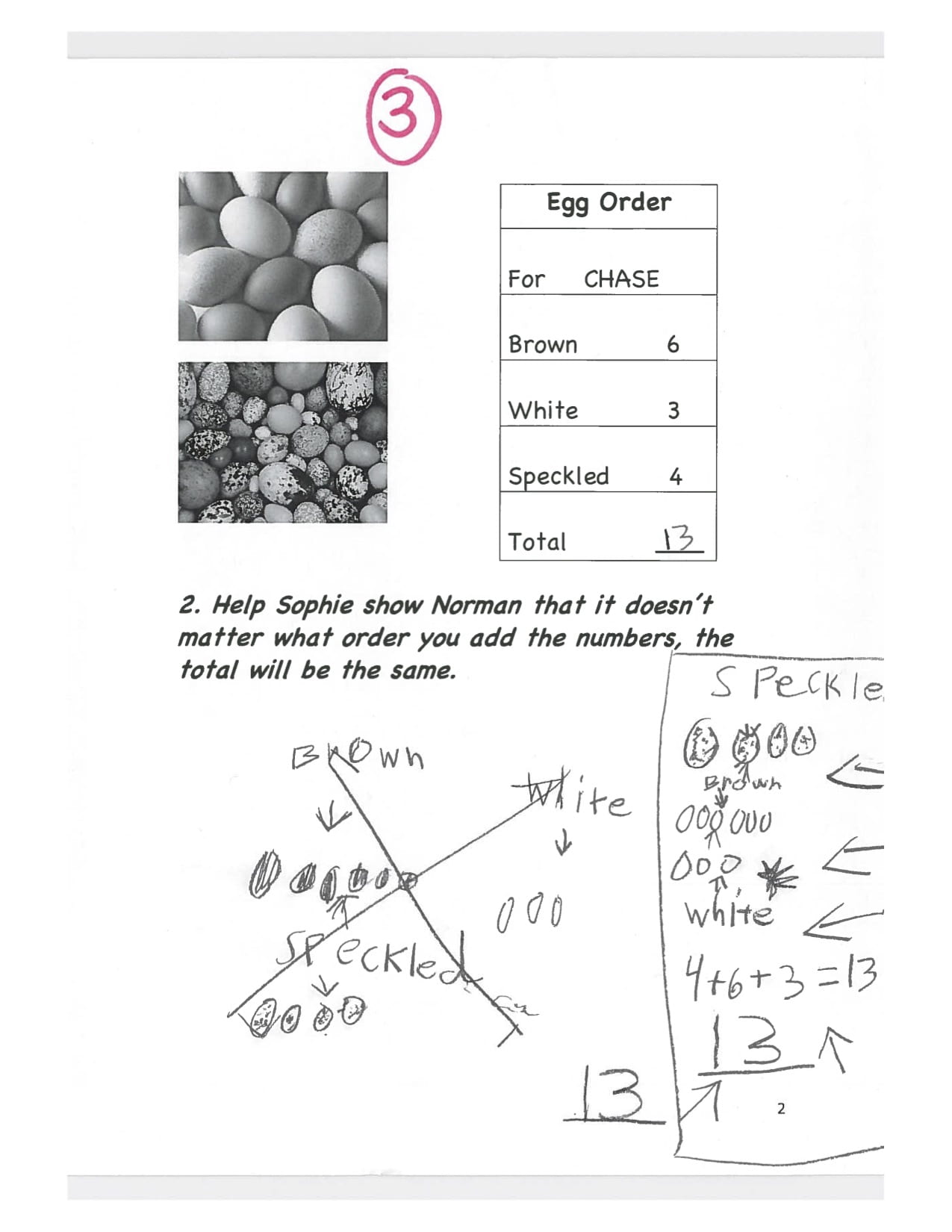

The work illustrated below is that of a first grader who struggles with math. In the story Sophie is trying to tell Norman that a good strategy for adding three numbers is to find the two you want to add first (often adding up to 10), then add the third. Norman thinks that he must add them in the order they appear on paper. The problem aims to help Sophie explain that the order of addition does not change the sum. (Thus, this problem asks first graders to prove the commutative property of addition.) The work below shows that the student understands what is being asked. The student first solves the problem in the given sequence, crosses it out, and then changes the order of numbers showing the total is the same. Pretty cool!

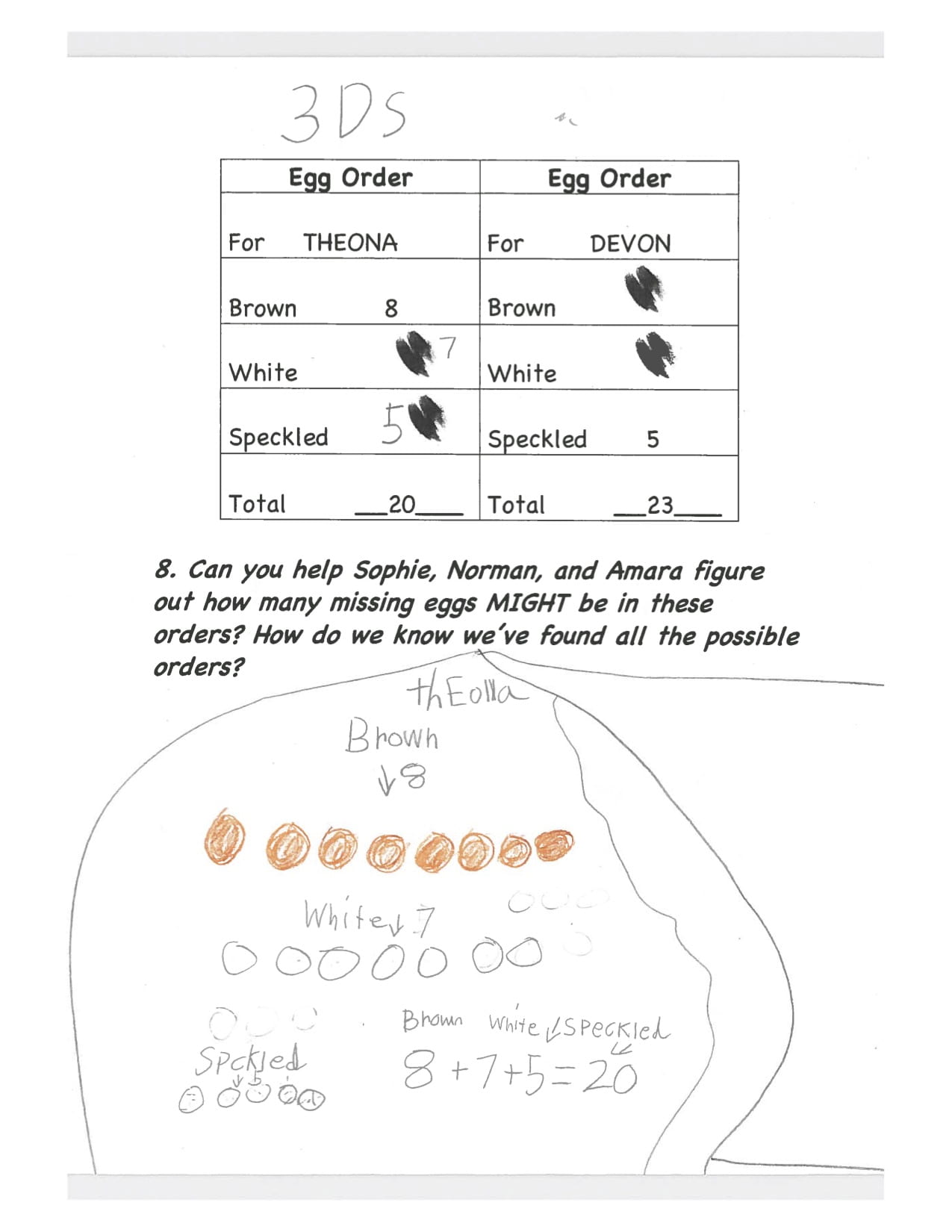

In the next example our first grader attempts to solve a problem with two unknowns. There are multiple “right” answers here. The solution below shows that the student has developed a working model and has come up with one solution to the problem. There are multiple representations and tools being used here: drawings, equations, labels, groupings, arrows. This is solid mathematical work and growth.

Teachers read the story as they would any other, pausing to ask and respond to questions about characters and situations. A story takes a week to complete. Each section within the larger story ends in a problem.

Teachers have to trust their students and the story.

Learners should be able to talk with their peers as they work on the problems. Because everyone is able to talk about the story, the classroom community serves as a source of support for a wide range of learner thinking. After working on a problem, the class is invited into a math conversation led by the teacher where different solutions and strategies are explored. However, the math stories do not work by themselves. Teachers have an essential role in making the stories successful. Through the joint efforts of teacher and student, an imaginative and impassioned understanding of math emerges, where through the power of story, mathematical concepts come alive.

Interested in Reading More?

It is not possible to convey the full nature of a math story in a blog post – the stories are long! Explore the website to learn more about how to use these stories and support the mathematical learning of your students by engaging imagination in learning. And, if you do visit the website, please tell us who you are so we can let you know about new stories as they appear.

Terrific! Both engaging and educationally valuable. Thanks!