By Kieran Egan (Emeritus Professor, Simon Fraser University)

By Kieran Egan (Emeritus Professor, Simon Fraser University)

Much, maybe most, of what one reads about imagination focuses on children, and on how we may help stimulate and develop their imaginations. We may also read a lot about how adult imaginations are crucial to creative work and to the general cognitive benefit of the mature person. But after childhood, and after maturity, most people still have a lot of life left to experience, during which we can hope to bound freely onto the sunny uplands of old age.

It is vanishingly rare that one sees research or writing about the imagination of the elderly. More likely one will see fretful descriptions of how sudoku or crossword puzzles can keep the mind active and help ward off dementia. I want here to reflect, rather, on how the imagination in old age has its own distinctive forms and possibilities, unavailable to those younger, or available only in attenuated modes. Yes, I heard your surprise at mention of old age’s “sunny uplands” as a description of what we have been taught to face with distress and regret. And regrets can hardly be avoided, like aches and faded powers, but other things also come along with extended life that can offer new dimensions of human experience.

It is vanishingly rare that one sees research or writing about the imagination of the elderly. More likely one will see fretful descriptions of how sudoku or crossword puzzles can keep the mind active and help ward off dementia. I want here to reflect, rather, on how the imagination in old age has its own distinctive forms and possibilities, unavailable to those younger, or available only in attenuated modes. Yes, I heard your surprise at mention of old age’s “sunny uplands” as a description of what we have been taught to face with distress and regret. And regrets can hardly be avoided, like aches and faded powers, but other things also come along with extended life that can offer new dimensions of human experience.

Behind the elderly person is a store of memory, knowledge, and a perspective across time that only age can give. One can, of course, simply sit idly through one’s final years and watch the light change in one’s room day by day, or one can harness the imagination to use one’s memory and knowledge in new ways. I have known, for example, an old man learning ancient Greek so that he could read Thucydides before he died, and met the mother of a friend sitting with her telescope and night-sky charts, learning the names of more stars and sketching the shape of our galaxy and the place of our home on one of its distant arms, and a couple extending their garden and encyclopedic knowledge of medicinal plants. Well, of course, these are hardly typical of the elderly, but in maybe lesser ways we can all extend our imagination’s reach while so much else seems to diminish. Though fingers may be arthritic, there’s likely an instrument one can learn to play, or return to, as is the case also with painting or photography. Limitations of energy and movement mean one might have to plan to do any of these things in restricted ways, but all arts are work with restricted means, tools, space, conventions; old age is just another accommodation to the means we use in expressing what we still can feel and imagine.

Behind the elderly person is a store of memory, knowledge, and a perspective across time that only age can give. One can, of course, simply sit idly through one’s final years and watch the light change in one’s room day by day, or one can harness the imagination to use one’s memory and knowledge in new ways. I have known, for example, an old man learning ancient Greek so that he could read Thucydides before he died, and met the mother of a friend sitting with her telescope and night-sky charts, learning the names of more stars and sketching the shape of our galaxy and the place of our home on one of its distant arms, and a couple extending their garden and encyclopedic knowledge of medicinal plants. Well, of course, these are hardly typical of the elderly, but in maybe lesser ways we can all extend our imagination’s reach while so much else seems to diminish. Though fingers may be arthritic, there’s likely an instrument one can learn to play, or return to, as is the case also with painting or photography. Limitations of energy and movement mean one might have to plan to do any of these things in restricted ways, but all arts are work with restricted means, tools, space, conventions; old age is just another accommodation to the means we use in expressing what we still can feel and imagine.

Imaginative Education has been commonly described through the cognitive tools through which it is articulated, and these have been tied, in part following Vygotsky, to language use. In old age we can find new stories to tell, or old stories to recall and tell anew, and we can learn to put emotions, memories, and long knowledge into words. Not perhaps the explorations of form so common with the young, or the energy of expression of the mature, but an older attempt to capture the moments past and present, and how they felt and feel.

Imaginative Education has been commonly described through the cognitive tools through which it is articulated, and these have been tied, in part following Vygotsky, to language use. In old age we can find new stories to tell, or old stories to recall and tell anew, and we can learn to put emotions, memories, and long knowledge into words. Not perhaps the explorations of form so common with the young, or the energy of expression of the mature, but an older attempt to capture the moments past and present, and how they felt and feel.  But, as also for the young, this is a learning process, in which one has to refashion one’s mature, and maybe diminishing, linguistic tool kit for new purposes. It requires discipline, but maybe at a pace that suits our strength, and more a refashioning of disciplines long developed through our lives, and particularly those developed in accommodating to the restrictions of old age.

But, as also for the young, this is a learning process, in which one has to refashion one’s mature, and maybe diminishing, linguistic tool kit for new purposes. It requires discipline, but maybe at a pace that suits our strength, and more a refashioning of disciplines long developed through our lives, and particularly those developed in accommodating to the restrictions of old age.

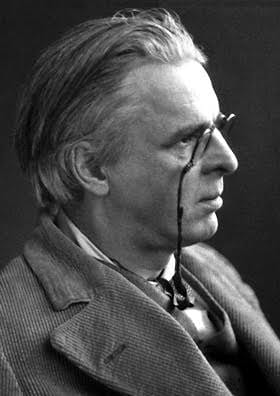

One value of poetry is that we all have its basic kitbag of words, and we have rhythms of language to explore and even if we have grown weary-hearted, it is some consolation to express the distinctive sense of one’s weariness, and how it grew. The great value of trying to write poetry is that, indeed, one will have to learn discipline and harness the energy and resolve to revise and revise and revise.  If old age is not something for the faint of heart, then anything we do in old age, if it is to be worthwhile, requires commitment and the readiness to learn, and the courage to recognize when we have failed to say just what we want. And, of course, one never finishes a poem; we abandon it when we can think of no way to make it better. Starting new work in old age also has the ambiguous pleasure of changing one’s perspective on the work one has done in the past. The longue durée enables one to take a different perspective on what some suppose are the serious accomplishments of one’s life and recognize them maybe as doubtful at best, and allow us to cast, as W.B. Yeats, recommended, a cold eye on them as we pass by.

If old age is not something for the faint of heart, then anything we do in old age, if it is to be worthwhile, requires commitment and the readiness to learn, and the courage to recognize when we have failed to say just what we want. And, of course, one never finishes a poem; we abandon it when we can think of no way to make it better. Starting new work in old age also has the ambiguous pleasure of changing one’s perspective on the work one has done in the past. The longue durée enables one to take a different perspective on what some suppose are the serious accomplishments of one’s life and recognize them maybe as doubtful at best, and allow us to cast, as W.B. Yeats, recommended, a cold eye on them as we pass by.  The longer perspective allows a widening of sympathy for the forms of life, art, and work one values, including one’s own, and also a widening critique. But this too is something only old age can truly know, and something you can hope to put into words, or paint, or music. Towards the end of the pilgrimage between our two eternities, the imagination and the arts can help us to become born anew and express our new perspectives and emotions in a multitude of ways, even if only, with W.B. Yeats, to “spit into the face of time / That has transfigured me.”

The longer perspective allows a widening of sympathy for the forms of life, art, and work one values, including one’s own, and also a widening critique. But this too is something only old age can truly know, and something you can hope to put into words, or paint, or music. Towards the end of the pilgrimage between our two eternities, the imagination and the arts can help us to become born anew and express our new perspectives and emotions in a multitude of ways, even if only, with W.B. Yeats, to “spit into the face of time / That has transfigured me.”

The old might smile wryly at the sonorous Romantic twaddle of Tennyson’s Ulysses, in which he wants the old warriors to smite again the sounding waves, but they now have lungs that can’t gasp enough air to carry an oar, let alone pull it across oceans, and they’ll have twisted backs and metal knees or hips, and stringy easily pulled muscles, but they could write about it as he did, or put it to music, or paint that dream. Tennyson’s Ulysses claims that:

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done.

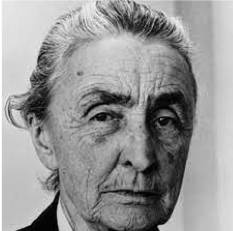

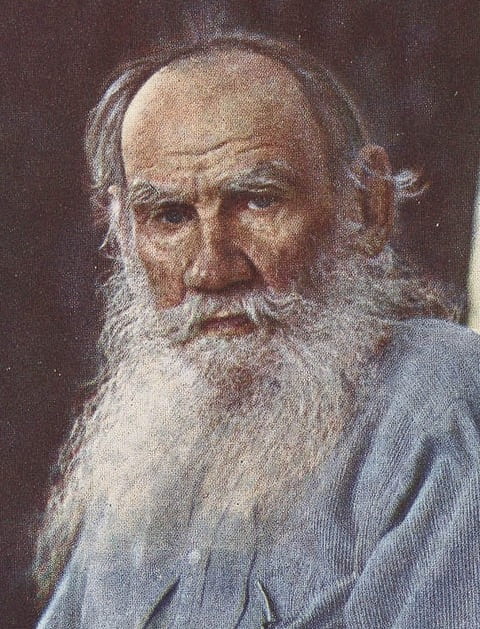

Well, maybe “noble note” isn’t quite what we are to aim for, but the struggle to express the unique vision of the world and experience that old age can attain provides its own rewards, and while public acclaim will properly attend rather to the achievements of the young and mature, the old writer, sifting through the “rag and bone shop of the heart” can accumulate a store of images and memories of value at least to friends and families, and perhaps also to others, and to the creative spirit still alive in age. (Mind you, don’t suggest reduced attainment where Leonardo, Rembrandt, Bach, Goethe, Tolstoy, Monet, O’Keeffe, Moses, Yeats, etc. etc. etc. are around.)

Well, maybe “noble note” isn’t quite what we are to aim for, but the struggle to express the unique vision of the world and experience that old age can attain provides its own rewards, and while public acclaim will properly attend rather to the achievements of the young and mature, the old writer, sifting through the “rag and bone shop of the heart” can accumulate a store of images and memories of value at least to friends and families, and perhaps also to others, and to the creative spirit still alive in age. (Mind you, don’t suggest reduced attainment where Leonardo, Rembrandt, Bach, Goethe, Tolstoy, Monet, O’Keeffe, Moses, Yeats, etc. etc. etc. are around.)

But even this might seem tinged with romantic twaddle when faced with old age’s not uncommon sinking towards dementia. But, even here, the imagination that has had much exercise in life, may carry consolations. Even Philip Larking, writing of “The Old Fools,” can find minimal reliefs:

Perhaps being old is having lighted rooms

Inside your head, and people in them, acting

People you know, yet can’t quite name; each looms

Like a deep loss restored, from known doors turning,

Setting down a lamp, smiling from a stair, extracting

A known book from the shelves; or sometimes only

The rooms themselves, chairs and a fire burning,

The blown bush at the window, or the sun’s

Faint friendliness on the wall some lonely

Rain-ceased midsummer evening. That is where they live:

Not here and now, but where all happened once.

Well, that’s just the minimal consolation elderly imaginations can hope for. Greater consolations come through starting new ways of writing, painting, photographing, creating music, and these need be no less rewarding than such achievements in the prime of life, augmented now by the additional recognition of the constraints against which they have been achieved.

* * * *

Kieran Egan’s first collection of poems, Amplified Silence, has just been published by Silver Bow Publishing. It is available from Silver Bow, your local bookstore, or from Amazon.ca and Amazon.com.

Those masterful images because complete

Grew in pure mind but out of what began?

A mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street,

Old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can,

Old iron, old bones, old rags, that raving slut

Who keeps the till. Now that my ladder’s gone

I must lie down where all the ladders start

In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.

W.B. Yeats.

We are like a rabbit in the evening

springing across a field

caught suddenly by the predatory hawk

* * * *

[Pictures of Leonardo da Vinci (assumed self-portrait, Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons, Source; Turin, Royal Library), Georgia O’Keeffe, Artemesia Gentileschi (self-portrait when young: Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons), Leo Tolstoy (Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons, photo 1908 by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky), Margaret Atwood (photo credit: Larry D. Moore, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons), W.B. Yeats (Public Domain, via Wikipedia Commons), Anna “Grandma” Moses, Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons.]

Interested in Reading More?

Kieran Egan has a wonderful new website humorously described by the author as “designed to describe my books and other writings and indicate where you can buy them, while modestly trying to persuade you how you’d enjoy reading them.” You can check out his new website here.

To read more of Kieran Egan’s work on imaginED, click any of the posts below:

Learning In Depth in a Franciscan Friary Cell

There’s Only One Answer And It’s Always Plato

Where Is The Song In The Heart Of Education?

Literacy And Driving In Screws With A Hammer

Do Schools Suppress Rather Than Encourage The Imagination?

“It Takes No Longer To Be Interesting Than It Does To Be Boring”

“The More You Know About Something The Easier It Is To Be Imaginative About It.”