By Karen M Effa (Educator, MEd in IE; IE mentor)

By Karen M Effa (Educator, MEd in IE; IE mentor)

It’s January 2021, and I am hunkered down at home amidst the ongoing covid-19 crisis. The New Year had not brought any relief to the isolation and strangeness of the new norms. As a support teacher, in a distributed learning school, convinced that the most memorable learning is often anchored in the somatic, what were my options? My students ranged from kindergarten to grade seven, and they were missing their friends, community classes, and face-to-face lessons. How could I help? What could I do to encourage my lonely students and facilitate some dynamic, interactive learning?

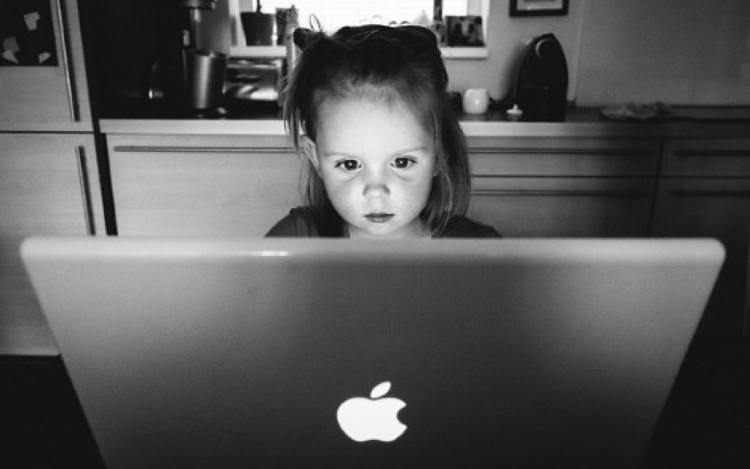

Although I appreciate the efficiencies that technology offers (when it works), I am not a screen enthusiast. There is something unnerving about the big eyes of a child, staring fixedly into a screen. It seems so terribly unnatural, but it was Zoom or nothing.

I decided to offer some classes for my students on ‘Understanding Multiple Perspectives’. It was also my personal exploration into the efficacy of Zoom. All grades were welcome in this pilot project, and I sentimentally named it ‘The Little Schoolhouse’. Although this learning would be virtual, I was determined to include as many cognitive tools from the somatic kind of understanding as possible. Would these tools offer the same engagement and meaningful learning that I had seen in the classroom? Would they work their same magic? Judson highlights that the five senses’ pedagogical importance is linked to their role in stimulating emotions and imagination (2015, Engaging Imagination in Ecological Education, p. 49).

The topic itself was challenging. Most adults struggle with understanding perspectives other than their own. In fact, often the attempt is not really made and the other person is seen as wrong or other. Yet globally, we need this ability desperately, in order to find solutions in our polarizing world.

One of the first things I tackled was to create personal connections between the students. Each week, they came prepared to share their answer to a question they had been given ahead of time. They were simple topics, such as, “When I go into an ice cream store, I choose _____, because ______.” “I wish I could visit _____, because ______.” As they took turns sharing their answers, they became better known as individuals, and as a group, listening to a variety of answers, we were reminded of inherent differences. All the students seemed to enjoy this low-stress way of participating.

Secondly, I delved into deepening their comprehension of the word ‘understand’; I wanted them to connect with the word emotionally, especially as it was at the centre of our topic and our heroic quality. This would only be possible if they connected the word to personal experience, so I took some linguistic liberties, creating a new word, ‘oversit’ (the opposite of understand J), and designed a poster. The ensuing conversations were personal and meaningful.

The ensuing conversations were personal and meaningful.

“To move the world we must first move ourselves.”

-Socrates

An essential skill, in pursuing understanding, is the acceptance that there is often more than one way to see something rightly. Here, the students worked through several sketching exercises. The first time, we all sketched an object I provided. Afterwards, holding up our sketches, we discussed why their sketches looked different from mine. I emphasized that our position to an object determines what we see. To further solidify this point, they sketched an object of their choosing, changing their position around it. We talked about how seeing something from different angles is not only true physically, but also in our thinking and feeling.

“We see the world, not as it is, but as we are.”

-Talmud

Understanding also requires humility and empathy. How could I give my students a personal experience of seeing someone or something in a new light? In other words, “to walk a mile in their moccasins” Well, I decided on a fir tree.

I shared my screen, and we discussed what they saw. Their comments were fairly superficial. I then asked them to pick up a weight and hold it horizontally, while we continued to discuss the tree. I dragged the conversation onwards, urging them to not lower their arm. I saw faces contorting and students switching to two-hand holds. Then I asked what was amazing about the fir tree. It didn’t take long before they pounced on the fir tree’s amazing ability to hold up its’ very heavy branches, with apparently no strain, 24/7. I don’t know if they will ever look at a tree the same way again.

I shared my screen, and we discussed what they saw. Their comments were fairly superficial. I then asked them to pick up a weight and hold it horizontally, while we continued to discuss the tree. I dragged the conversation onwards, urging them to not lower their arm. I saw faces contorting and students switching to two-hand holds. Then I asked what was amazing about the fir tree. It didn’t take long before they pounced on the fir tree’s amazing ability to hold up its’ very heavy branches, with apparently no strain, 24/7. I don’t know if they will ever look at a tree the same way again.

Having anchored the learning in the somatic, I also added a cognitive tool from the Mythic kind of Understanding. Having providing experiences that I hoped moved them emotionally, we watched stories via Youtube that also specifically focused on seeing a situation or person from a different perspective. (Please see links for these stories at the end of this blog.) When I run these classes in the fall, I plan on adding a musical experience, to emphasize how familiarity can influence our preferences. Differences may just flow from norms other than our own.

It had been a success. Even on a virtual platform, the somatic cognitive tools engaged the students and provided meaningful and personalized learning. Their understanding of the importance of recognizing and validating multiple perspectives had been deepened. Perhaps most importantly, I had learned that authentic learning can happen virtually; although I am still really looking forward to being in a classroom again soon.

Online Resources:

*Featured Image by zeitfaenger.at

Interested in Reading More?

Interested in Reading More?

Check out Karen’s other posts on the somatic in her “Spotlight on the Somatic” series: