By Gillian Judson

The goal for any healthy organization is to create epidemics of imagination.

(Liu, E. & Noppe-Brandon, S., 2009, pp. 207-208)

In Imagination First: Unlocking the Power of Possibility (2009) Eric Liu and Scott Brandon (formerly Noppe-Brandon) consider what it would take to establish imagination as a norm in a community. They suggest that if we want to institutionalize imagination we must think in terms of epidemics. They ask:

What are the initial environmental conditions that enable a virus to live and spread? How do institutions act to make people more or less susceptible to the virus? When the virus first spreads, what are we taught to do to contain it? How are we told this? Now, imagine that the virus is imagination. Instead of trying to contain the virus, imagine what you’d do to accelerate its spread. How would you nurture its earliest forms? What would you do to lower the community’s resistance to it? How would you help the virus adapt to the anti-imagination treatments and to grow even fiercer? (pp. 207-208)

ep·i·dem·ic / epəˈdemik/

~ a widespread occurrence of an infectious disease in a community at a particular time

An epidemic of imagination?

This metaphor caused me to pause when I first read it in 2018. Now, two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, it stops me in my tracks. In 2018 I thought it was unusual—and somewhat inappropriate—to compare the spread of imagination with the spread of disease. Epidemics harm. Disease hurts. I was also uncomfortable with the sense of danger that can so often be associated with the word epidemic. Now, with new learning and research under my belt, I find this a compelling comparison.

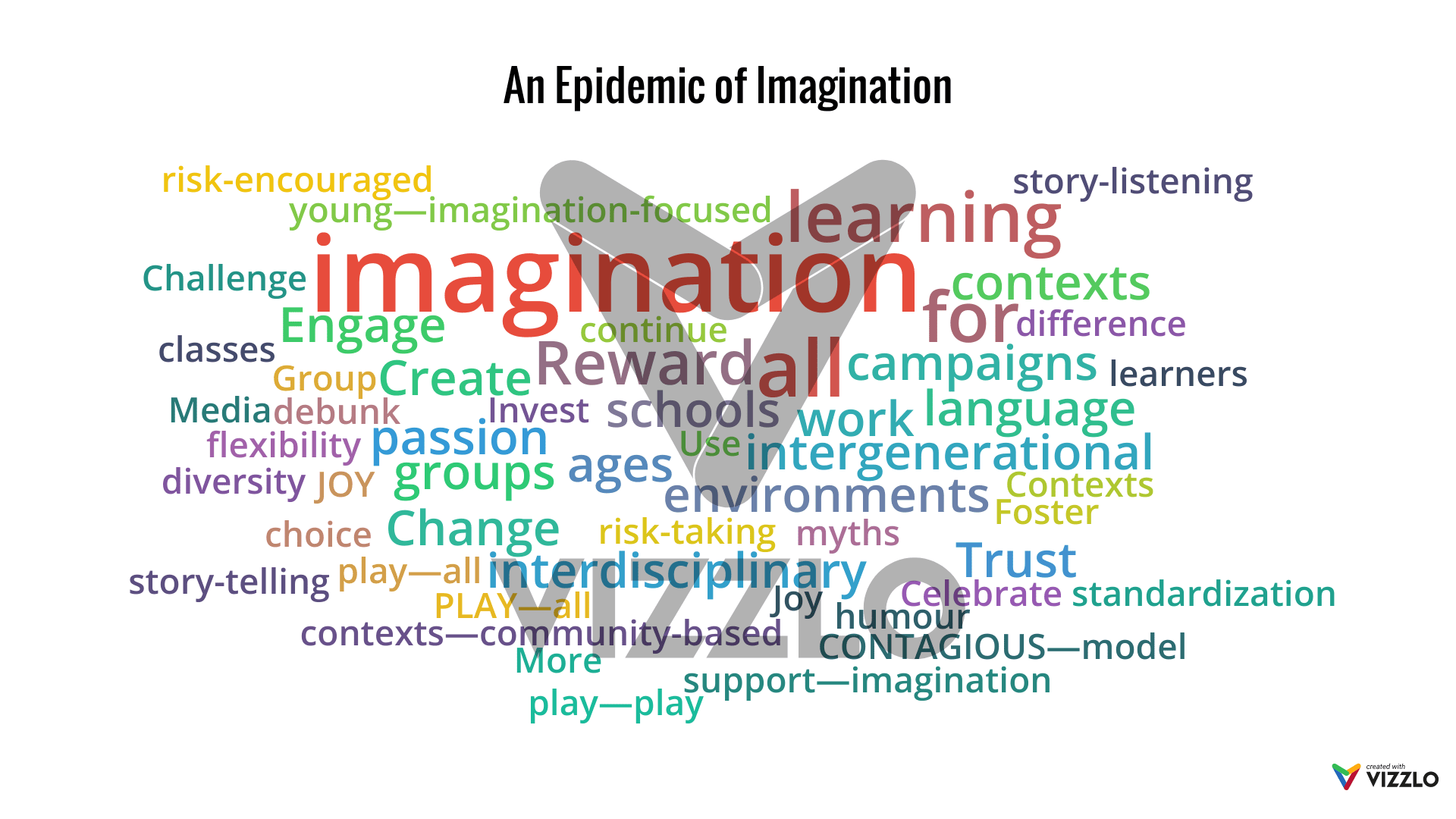

This post explores this metaphor and invites you to do the same. I also share my undergraduate education students’ responses to Liu and Brandon’s questions about how to fuel an epidemic of imagination. These students were all enrolled in a 4th year course that explores the complexities of the curriculum studies field. In this course I introduce the often-neglected concept of imagination to the complicated conversation that is curriculum. I strive to teach about imagination and with imagination. So, in one class near the end of the term, I asked my students to think in terms of epidemics. This post offers a snapshot of what they said. By engaging them with this imagined scenario—a small change of context in the classroom—I was able to tap into their sense of the possible and assess what they understand about imagination. What stands out to me from their responses is that institutionalizing imagination requires debunking myths about what imagination is and does, changing the language around imagination we use in our communities, playing more, and embracing diversity.

im·ag·i·na·tion /iˌmajəˈnāSH(ə)n/

~ the ability to conceive of the possible in all things; the generative feature of mind out of which all creativity and innovation grow (Judson, 2021)

Engaging Metaphors

When considering COVID, Ebola, or SARS, epidemics do indeed cause harm in myriad ways. But what if a community is facing the uncontrollable spread of a contagious practice of kindness? or generosity? What if a practice of daily walking infects a whole population? What if whole communities are afflicted with selflessness? What if an epidemic of imagination sweeps through an organization? Personally, I wouldn’t mind living through an epidemic of kindness, selflessness, or imagination. I am willing to live with that new normal. I love the sense of contagion that this metaphor involves.

When it comes to more typical epidemics the virus is “the enemy”—we battle them, we surround them, we try to contain them. For some, imagination is also a threat. Imagination threatens to move us away from the status quo, to question the “ways we always do it”, to destroy well-established and often unquestioned beliefs about learning, school, and leadership. Imagination can cause dis/ease and dis/comfort. It urges us to think differently in contexts that may not accept mistakes, let alone reward them. It can leave us worried if we consider ourselves “unimaginative” or if we mistakenly think imagination is a possession of the few. Imagination can cause a sense of dis/ease as long as it is misunderstood. I like how this metaphor caused me pause—it engages my imagination.

When it comes to more typical epidemics the virus is “the enemy”—we battle them, we surround them, we try to contain them. For some, imagination is also a threat. Imagination threatens to move us away from the status quo, to question the “ways we always do it”, to destroy well-established and often unquestioned beliefs about learning, school, and leadership. Imagination can cause dis/ease and dis/comfort. It urges us to think differently in contexts that may not accept mistakes, let alone reward them. It can leave us worried if we consider ourselves “unimaginative” or if we mistakenly think imagination is a possession of the few. Imagination can cause a sense of dis/ease as long as it is misunderstood. I like how this metaphor caused me pause—it engages my imagination.

And so I wondered: What would my undergraduate students say about how to encourage epidemics of imagination in post-secondary contexts?

Changing The Context: Thinking Epidemics with Undergraduate Students

I told my students to try to forget COVID-19 for the time being. The virus of concern was now imagination. Our goal? Community spread. Some brief instructions:

Instead of trying to contain imagination (the virus), imagine what you’d do to accelerate its spread.

Here is what they said:

How would you nurture its earliest forms?

- Transform K-12 education to be imagination-focused—that is, a central aim is the growth and enrichment of all learners’ imaginations to enrich academic learning

- Encourage possibility-thinking and perspective-taking in learning

- Teach storytelling and storylistening skills to all learners (required courses) K-postsecondary

- Learn about Indigenous storywork and how one can become “storywork ready” (Archibald, 2008)

- Foster risk-taking in risk-encouraged environments

- Encourage free play AND play-fullness in learning (humour, flexible thinking, irony) for all ages of learners

- Fund public campaigns to address widespread misconceptions about imagination (e.g. the myths that imagination is only for kids, is only a possession of the few, or contributes to arts but not math or sciences)

- Fund a “We Are Imagination” movement

- Maximize student choice in terms of how they engage with topics and how they “show what they know” and challenge initiatives that standardize learning

- Invest in new stories of what “school” is and what it can/should look like

- Employ imagination mentors to support and expand practical understanding of imagination

- Invest in outdoor classrooms to change the context of learning

- Create What if taskforces in every school district that examine policies and processes

- Ensure imagination-focused teacher education

- Invest in opportunities for interdisciplinary and intergenerational learning

- Ensure educational leaders model imagination

Source: Vizzlo

What would you do to lower the community’s resistance to it?

- Employ new metaphors for imagination to change perspectives and address misunderstanding (e.g. imagination as soil (Judson, 2021))

- Form interdisciplinary focus groups and task forces in different industries that research the role and potential of imagination

- Nurture risk-taking in organizations

- Provide community-based and interdisciplinary demonstrations of imagination

- Provide community-based classes on imagination and what tools can cultivate it

- Fund widespread public information campaigns

- Require all public employees to have imagination training

- Teach the language of imagination and Imaginative Education—cognitive tools and how these cultivate imagination

- Address false binaries: science vs art; reason vs imagination

- Address feeling—focus on value/need for emotions

- Instate a Ministry of Imagination (Hopkins, 2019)

- Reward innovative responses

- Reward proposals for change

- Provide tax rebates for adult PLAY

How would you help the virus adapt to the anti-imagination treatments and to grow even fiercer?

- Engage our agency—we are imaginative beings and REQUIRE contexts that value this

- Create support groups—create lobby groups for imagination accomplices to connect and learn

- Organize transdisciplinary and intergenerational events and opportunities

- Reward play in organizations

- Require all university students to study imagination in 1st year—then all further courses engage and expand on imagination—practical applications

Final Thoughts

My students’ responses indicate that if we want an epidemic of imagination, we need to be able to understand what imagination is and does for humans. One of the reasons imagination isn’t rapidly spreading through our communities is because it is misunderstood. We need infected people to help the spread by modeling imagination in action, showing the subtle and not-so-subtle ways in which it contributes to human life. We need imagination accomplices to work across contexts to identify imagination’s roles, and its values, in all disciplines. In this way, we might better understand the myriad ways that imagination is manifest and how it works for all people.

References

Archibald, J. (2008). Indigenous Storywork. UBC Press.

Hopkins, R. (2019). From what is to what if: Unleashing the power of imagination to create the future we want. London: Chelsea Green Publishing

Judson, G. (2021). Cultivating Leadership Imagination with Cognitive Tools: An Imagination-Focused Approach to Leadership Education. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 19427751211022028.

Liu, E. & Noppe-Brandon, S. (2009). Imagination first: Unlocking the power of possibility. Jossey-Bass.