By: Dr. Kieran Egan

Dwelling on triumphs past, which doesn’t take long, I recalled a talk I had to give in Dublin some years ago on the creative imagination and its place in the arts and sciences. I started my talk by noting that having a creative imagination has been described as a consequence of a wound received in childhood that doesn’t heal. My theme was that while it may not be easy to work out how to help people become more imaginative, there are ways in which we can easily inhibit imaginations, with or without wounds in childhood.

One sentence in the question and answer session after the talk evoked the most powerful spontaneous applause of anything I have ever said.

Those who were present greeted the sentence first with a moment of silence, and then a spontaneous roar filled the hall from the delegates and many were on their feet applauding and shouting agreement for what seemed like an embarrassingly long time. It was embarrassing also because the claim I had dramatically made was plainly false.

Perhaps you’d like to know what the sentence was?

Well, I should first set the scene a bit more. The conference delegates were mostly prominent artists and scientist from Ireland and the UK, with some from the continent and only a few from North America. There were also some educational policy makers, and a few politicians. So, a little bit intimidating. Mine was the first talk, in a rather splendid room with high ceilings, elegant drapes beside the windows, sets of white-clothed tables, and the tightly packed hundred-plus audience around them. When I stood up I was a bit disconcerted to see myself at the back of the room reflected from a fine, ornately framed mirror, which in turn reflected the large and fine mirror behind me. I had the curious sensation of my words somehow disappearing into the gray opaqueness of my endlessly fading images, front and back, curving gradually away to the right, with the sense that reality was somewhere in their dark interior, distant from the bright illusion of the room.

The provocative question I was asked concerned why schools seemed to suppress rather than encourage imaginative intelligence. Consciously being a little reckless my reply began with:

“The school is the most anti-intellectual institution in our society.”

I didn’t get any further because the shouted agreement from this group of scientists and artists drowned out the possibility of my going on to acknowledge that the claim was plainly absurd and reflected an ignorant prejudice many had about schools, and also prevented me from indicating the part of it that seemed to be defensible. What became awkwardly clear in their response to the wild idea, which they had perhaps not previously articulated in their own minds, was that it captured exactly what most of them clearly believed.

Their belief seemed a product of their own experience, in which schools were failing to educate students adequately to sustain suitable work in the arts and sciences. To them, we were in an educational crisis, and the schools were failing to do their proper part in responding to it. There was much talk at the conference about the hostility of schools to intellectual life, and their encouragement of dumbing everything down, as those scholars saw it, to the crudeness common in our public media.

One response many educators would make to the hostility expressed at that conference is that those artists and scientists had an old-fashioned, elitist, “traditionalist,” view of the role of schools. One of the arguments made early in the previous century in the successful movement we call “progressivism” was that the proper role of schools was to prepare students for the life they were to lead in a modern democratic society, not narrowly prepare the most successful at academic tasks for higher education.

One result of the success of that old progressivist argument was the very rapid disappearance of subjects like Latin from the regular school curriculum. And one result of that was, for example, that apparently hardly anyone now recognizes that “media” is a plural, so we may read or hear that “The media is going mad about Kim Kardashian’s latest outing with Caitlyn.” To some this matters—the grammar, that is, not the Kardashian performance—and to others it is just an example of how language develops and certainly nothing to worry about.

The claim that the school is the most anti-intellectual institution is society is clearly absurd at one level—less intellectual than banks, the auto-industry, showbusiness? But the slur hurt because of a suspicion that something has gone amiss in the purposes of schools.

If the 20th century deal was that schools would significantly abandon academic education in favour of increasing its social role in preparing students for everyday life and work in a democratic society, it’s not obvious that school are being particularly successful. Sacrificing Latin for social benefits may be a good deal, but not if we finish up with no Latin and no obvious improvement, and perhaps even a diminution, in social benefits from schooling.

I suppose what is troubling me is that while educators’ struggle with their mounting daily concerns, and the huge increase in demands made by endless “stakeholders”, they have little time or energy or patience to deal with questions about the proper roles of schools. What is also troubling is that surprising “triumph” in Dublin, and my concern about what most teachers and educational administrators would make of that roar of agreement that the school is the most anti-intellectual institution in our society.

Of course it is tiresome that so many groups complain about schools, and demand more driver-preparation, drug counseling, economic literacy, health training, bullying control, and so on—but that’s what you get if you go along with the sacrifice of the definable academic role of schools in favour of imprecise and enlarged social purposes.

So, a rather bitter “triumph.” The Dublin scientists’ and artists’ distress at schools should not, however, be ignored, and nor should the common response that those elite achievers don’t understand the complex roles of schools today. But those old complaints and responses will hang around unsatisfactory to all until we bring some creative imagination to reconceiving the roles of schools, whatever might be individual teachers’ heroic roles in the great work of educating the young.

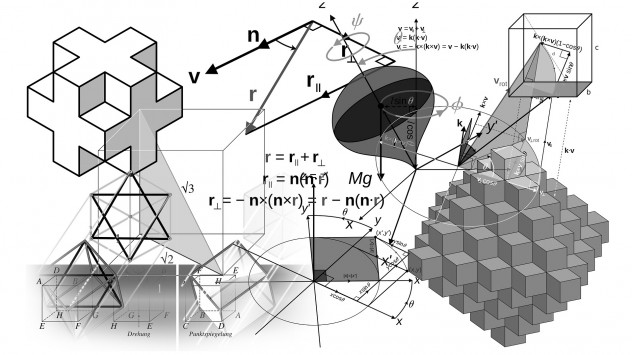

One problem we have inherited from the 20th century “curriculum wars,” fought over the amount of time and effort given in schools to academic content or matters of social utility or encouragement of individual free exploration, is that we come to see these things as mutually incompatible; as in competition or conflict with each other.

If we see the development of creative imaginations as a crucial role of schooling we have to recognize that students’ enlivened imaginations have to work within, be alert to, and benefit, the social realities of our time and place, and that students need space, time, and freedom to explore possibilities, and that their imaginations can work only with what they know, and the more they know the richer the range of effective imaginative possibilities they can generate.

So how can these three purposes of schooling be attained without their each tripping over the others?

The imaginED blog is dedicated to showing how “cognitive tools” are keys to developing imaginations.

When people outline what they want from 21st century education, and describe 21st century learning, there is often something of a letdown when one looks at the proposals for bringing these about—too often they simply dress up old progressivist ideas in bright new clothing. It is perhaps worth reflecting on how the cognitive tools that constitute central features of the Imaginative Education approach can actually ignite genuinely new 21st century learning that stimulates rather than suppresses students’ imaginations, and achieve those often mentioned aims of 21st century education.

Don’t miss a thing.

Get a weekly email from imaginED with a summary of our posts–free resources, lessons, and ideas for imagination-focused teaching. Join other educators concerned with maximizing learning in their classrooms. Subscribe today!

Other posts by Dr. Kieran Egan:

“The more you know about something the easier it is to be imaginative about it.”

“It takes no longer to be interesting than it does to be boring.”

There’s only one answer and it’s always “Plato”

Literacy and driving in screws with a hammer.